This article was written by Michael Barrett at the University of Glasgow, and was originally published by The Conversation.

As if years of war, terrorism and oppression weren't harrowing enough for the people of Syria, the country is experiencing an epidemic of a so-called flesh-eating disease. Outbreaks of the disease, known as leishmaniasis, have been reported repeatedly over the past year.

More recently, the head of the Kurdish Red Crescent was reported to have said the problem was made worse by the actions of Islamic State leaving bodies to rot in the streets. But while leishmaniasis is a serious problem in Syria, this picture of a flesh-eating disease spread by terrorists isn't entirely accurate.

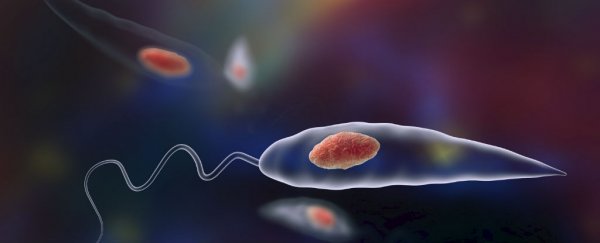

Leishmaniasis has actually been endemic to Syria for centuries and was once commonly known as "Aleppo evil". This cutaneous (skin-affecting) form of the disease isn't strictly 'flesh eating', although another form found in Brazil and some other parts of South America can be. It is caused by the Leishmania parasite, which is carried by sandflies. If you're bitten by a fly, the parasites can enter your blood and invade the macrophage immune cells that normally kill bugs, causing causing horrible open sores close to the bite.

In other places, in particular India, a different form of the parasite spreads to the liver and spleen and causes death as those vital visceral organs break down. In the Brazilian form, the parasites cause macrophages to migrate to the mucosal surfaces around the mouth and nose. Here the immune system attacks the parasites but ends up causing substantial damage to surrounding tissue, eating away the flesh in these areas, leading to gross disfigurements.

Sandflies actually don't eat rotting bodies on the street, they suck blood from living people, so the reports about Islamic State spreading the disease aren't strictly true. However, the political events in Syria - including the rise of Islamic State - have caused the collapse of the country's health systems, along with every other part of the social structure there. So inevitably, the disease has been spreading more widely.

Can it be treated?

Today, around 1.3 million people are infected with leishmaniasis every year across the tropics and sub-tropics. Most sufferers have the cutaneous form, as found in Syria, while the visceral form can be fatal. But because it is typically found among the world's poorest people, it receives little attention in terms of developing new drugs or vaccines and is considered a neglected tropical disease.

However, treatments do exist and in a functioning health system drugs can be used to cure the disease. Scientists are still debating the best treatment for the cutaneous disease but at present we have four different drugs that can be used. The best medicine for visceral leishmaniasis is called amphotericin B and when injected it is very efficient at curing the disease. Just a few injections of the drug can be enough to cure the disease, but it does carry the risk of side effects such as fever, headaches and vomiting.

Older drugs have to be given for several weeks to show an effect. For example, when TV adventurer Ben Fogle caught the cutaneous disease in Peru a few years ago he was treated with a rather toxic antimony-based drug, which made him feel very ill and lose large amounts of weight but eventually cured him.

Could it spread more widely?

In addition to the increasing incidence of the disease in Syria itself, some refugees fleeing the country will carry parasites with them. This could be used by those who oppose taking in refugees by suggesting they will spread disease. But countries receiving refugees need not worry about its introduction.

It is sandflies, not people, that transmit the disease and though they are found throughout the tropics and subtropics, they can't survive in colder climates. The visceral form of leishmaniasis is already endemic in parts of southern Europe including Spain, Italy and the south of France, but the disease tends to only manifest itself in people with weak immune systems such as those infected with HIV. This highlights the fact that people in prosperous regions where nutrition and general health are good are at limited risk.

It is also important to understand that different species of sandfly are responsible for transmission of different Leishmania parasites. Those that transmit the cutaneous disease found in Syria are less common in southern Europe so the chances of increasing transmission of cutaneous leishmaniasis are small. Although Turkey might be at risk of increased incidence of the cutaneous disease due to the flow of refugees from Syria, again it is worth highlighting that people with access to good nutrition and in generally good health are less vulnerable.

Concerns about imported germs, of course, are nothing new. Just last year, European airports were decorated with posters warning of Ebola, and those coming from West Africa were subjected to mandatory tests for signs of fever. But we should be careful of warnings of diseases spreading to developed countries, where healthcare systems and levels of public health are much more capable of preventing and treating infectious condition, even in instances where those diseases could spread. Plus the wider availability of treatments in Europe creates an opportunity to provide healthcare to incoming sick refugees.

Given that leishmaniasis cannot be spread to colder countries and is limited by good healthcare, the particular suggestion that it could be carried by refugees holds no force.

![]() Michael Barrett, Professor of Biochemical Parasitology, University of Glasgow.

Michael Barrett, Professor of Biochemical Parasitology, University of Glasgow.

This article was originally published by The Conversation. Read the original article.