Researchers have discovered radioactive debris from a series of massive supernova explosions at the bottom of Earth's largest oceans, dating back to between 3.2 and 1.7 million years ago - relatively recently, in astronomical terms.

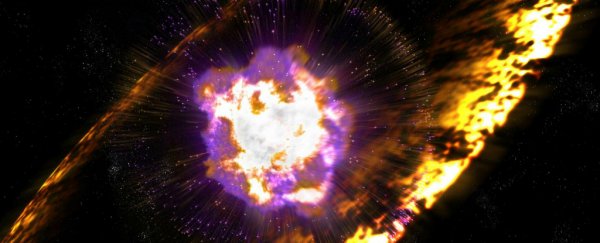

Supernovae are huge explosions that occur when stars run out of fuel and collapse in on themselves, blasting heavy elements and radioactive isotopes across space. And the newly discovered fallout left behind on Earth suggests that around 3 million years ago, a rapid series of explosions occurred, lighting up the sky and bombarding our planet with debris - and potentially changing the climate.

"We were very surprised that there was debris clearly spread across 1.5 million years," said lead researcher Anton Wallner from the Australian National University. "It suggests there were a series of supernovae, one after another."

"It's an interesting coincidence that they correspond with when Earth cooled and moved from the Pliocene into the Pleistocene period," he adds.

Hints of this series of explosions were first found around a decade ago, when Wallner discovered traces of an isotope called iron-60 in samples taken from the Pacific Ocean floor.

Iron-60 is only produced in giant space explosions, and has a much shorter half-life than the stable iron-56 atoms found here on Earth. Intrigued as to how the iron-60 isotopes might have ended up there, Wallner has since been searching for traces of similar interstellar dust in 120 ocean-floor samples collected from around the world.

His team found that iron-60 was actually scattered across Earth in two distinct time periods: 6.5-8.7 million years ago, and 3.2-1.7 million years ago. This suggests that during those time periods, a nearby supernova (or supernovae) blasted us with debris.

And speaking of coincidences, the older explosion that occurred around 8 million years ago also coincided with a time of global faunal changes in the late Miocene period, adding more weight to the idea that supernovae might have an impact Earth's conditions.

The researchers aren't exactly sure how nearby supernovae could change the planet's climate or affect life - the radiation blasted out would have been too weak to cause any direct biological damage or mass extinctions (just FYI, a supernova would need to be about 26 light-years away in order to do that).

But scientists have hypothesised for decades that supernovae could be influencing our planet, and one of the leading ideas is that the cosmic rays blasted out by the explosions could increase cloud cover or impact the climate by burning up in our ozone layer, which could explain some of the changes that happened around the same time.

"We don't have any concrete evidence that any one event is tied to a supernovae," University of Kansas astronomer Adrian Mellott, who wasn't involved in the study, told Maddie Stone over at Gizmodo. "But the odds are, one or more are."

While more research needs to be done to figure out the potential link, what's even cooler is that the scientists calculated that the most recent series of supernovae would have occurred in an ageing star cluster around 326 light-years away at the time.

That means the explosions would have been small, but as bright as the Moon - so if we were around back then we would have actually been able to see them light up the sky as they happened. And that's pretty incredible to imagine.

The research has been published in Nature.