A vast patch of abnormally warm water in the Pacific Ocean - nicknamed the blob - resulted in increased levels of ozone above the Western US, researchers have found.

The blob - which at its peak covered roughly 9 million square kilometres (3.5 million square miles) from Mexico to Alaska - was assumed to be mainly messing with conditions in the ocean, but a new study has shown that it had a lasting affect on air quality too.

"Ultimately, it all links back to the blob, which was the most unusual meteorological event we've had in decades," says one of the team, Dan Jaffe from the University of Washington Bothell.

The blob of warm water in the Pacific was first detected back in 2013, and it continued to spread throughout 2014 and 2015. While it was less obvious in 2016, there were some indications that it persisted well into last year too.

The vast, warm patch has been linked to several mass die-offs in the ocean during 2015, including thousands of California sea lions starving to death in waters more than 3 degrees Celsius (5 degrees Farenheit) above average, and an "unprecedented" mass death of seabirds in the Western US.

In April 2015, the effects could also be seen on land, with a bout of strange weather in the US being linked to the higher ocean temperatures, and the increased temperatures saw a massive toxic algal bloom stretch along the entire US West Coast.

"I can't truly give an explanation of what is going on right now," marine ecologist Jaime Jahncke from conservation group, Point Blue, said in late 2015.

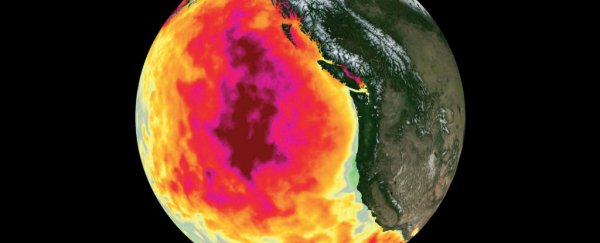

Unusually high sea-surface temperatures in the Pacific in May 2015, compared to the 2002-2012 average. Credit: American Geophysical Union

Unusually high sea-surface temperatures in the Pacific in May 2015, compared to the 2002-2012 average. Credit: American Geophysical Union

Jaffe and his team have been monitoring ozone levels over the US since 2004, and happened to noticed a bizarre spike in 2015. They wondered if the crazy events linked to the blob that year could also have been driving this massive boost in ozone.

"At first we were like 'Whoa, maybe we made a mistake.' We looked at our sensors to see if we made an error in the calibration. But we couldn't find any mistakes," Jaffe says in a press statement.

"Then I looked at other ozone data from around the Pacific Northwest, and everybody was high that year."

To see if there was a connection, the team mapped the lifespan of the blob in unprecedented detail, using multiple satellites positioned all over the globe to track temperature fluctuations on the Pacific Ocean's surface between 2014 and 2016.

They then went back and compared the events to sea-surface temperature records dating back to 1910, and what they found was unlike any natural phenomenon ever seen in recorded history.

"This phenomenon is something new," one of the team, Chelle Gentemann from Earth and Space Research in Seattle, told National Geographic.

"From that entire record, this event is unprecedented in magnitude and duration. There's just nothing like it in our historical record."

They found that the effects of the blob on land - warmer temperatures, low cloud cover, and calmer air - actually combined to produce extra ozone, and by June 2015, this had pushed ozone levels to between 3 and 13 parts per billion higher than average over the northwestern US.

Certain areas with already high ozone levels, such as Salt Lake City and Sacramento, saw their ozone pushed above federally allowed limits.

"Washington and Oregon was really the bullseye for the whole thing, because of the location of the winds," Jaffe explains.

"Salt Lake City and Sacramento were on the edge of this event, but because their ozone is typically higher, those cities felt some of the more acute effects."

So how does something in the ocean affect our ozone levels?

Under normal conditions, winds along the West Coast run along the surface of the ocean, and push the top layer away from the coast. This allows the colder water below to take its place, bringing vital nutrients with it, and balancing out the temperature.

But the team found that during the blob's peak, the increased temperatures on the surface of the ocean had caused the air above heat up and stagnate. This weakened the coastal winds so much, they were no longer able to push the warm top layer of the Pacific away from the shoreline.

And with no upwelling of cool water, the high temperatures remained, and together with a lack of clouds, this allowed the chemical reaction that produces ozone - solar ultraviolet radiation (sunlight) breaking down oxygen molecules - to kick things up a notch.

"Temperatures were high, and it was much less cloudy than normal, both of which trigger ozone production," says Jaffe.

"And because of that high-pressure system off the coast, the winds were much lower than normal. Winds blow pollution away, but when they don't blow, you get stagnation and the pollution is higher."

While the ozone spike was only temporary, the team says we should take this as a warning for the future - researchers already knew there was a connection between higher atmospheric temperatures and ozone production, but now we know that sea-surface temperatures can affect it too.

And with ozone pollution known to cause serious respiratory dysfunction, including aggravating pneumonia, asthma, and bronchitis, we'd better be prepared for when something like the blob rears its head once more.

The research has been published in Geophysical Research Letters.