Scientists have been monitoring a fracture in one of the world's biggest ice shelves, and report that in the last five months alone, it's grown an extra 22 kilometres (13.67 miles) in length, and now stretches for a total of 130 km (80 miles).

It's now only a matter of time before a massive chunk of this Antarctic ice shelf - known as Larsen C - breaks free, and then we'll have the third largest loss of Antarctic ice in recorded history on our hands.

Located on the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, the Larsen ice shelf is split up into three smaller ice shelves - Larsen A, B, and C. Larsen A and B have already experienced massive declines over the past two decades, and now Larsen C, the biggest of them all, is in a world of trouble itself.

Researchers from Project MIDAS, a British Antarctic Survey that involves teams from several UK universities, report that around 12 percent of the entire Larsen C ice shelf is expected to break off, leaving the exposed ice front at its most retreated position ever.

"Computer modelling suggests that the remaining ice could become unstable, and that Larsen C may follow the example of its neighbour Larsen B, which disintegrated in 2002 following a similar rift-induced calving event," they report in a blog post.

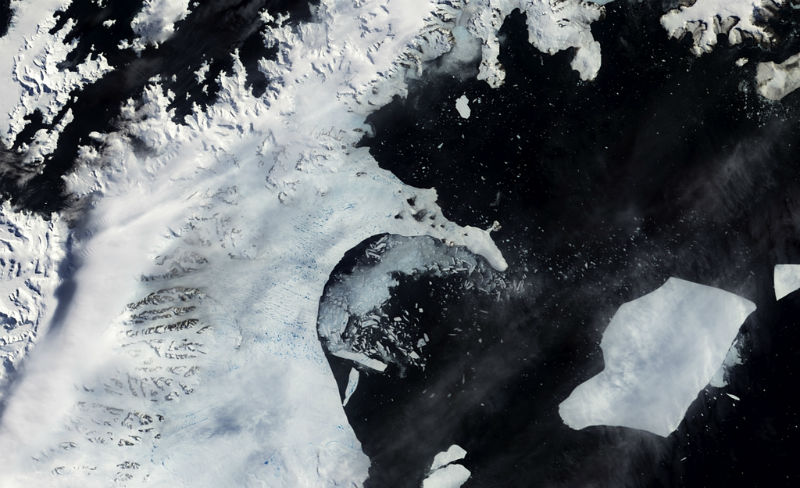

What's left of the Larsen B ice shelf is widely considered to be on borrowed time, having lost a chunk of ice the size of Rhode Island back in 2002. Remember this?

Larsen B ice shelf loss in 2002. Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Centre

Larsen B ice shelf loss in 2002. Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Centre

It now covers an area of 1,600 square kilometres (625 square miles), and is expected to disintegrate by the end of the decade. That's pretty devastating, when you consider that Larsen B has been stable for at least the past 12,000 years.

The Larsen A ice shelf disintegrated in January 1995, and now Larsen C looks like it's on its way out too.

Just to give you an idea of how much ice we're talking about here, Larsen C covers around 55,000 square km (21,235 square miles). That's 10 times the size of Larsen B, and about half the size of Iceland.

Last year, the MIDAS team published a study in the journal Cryosphere describing how Larsen C is currently melting from the surface and the base, and now its gigantic fracture is cracking at a rate no one could have predicted.

Once the outer edge breaks free, researchers are predicting an iceberg measuring about 6,000 square kilometres (2,316 square miles) - close to the size of Delaware - will fall off into the ocean.

"If this will calve off in the next, say two or three years, the calving front will be retreated very far back, further than we've seen it since we were able to monitor this," one of the team, Daniela Jansen from the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research in Germany, told Chris Mooney at The Washington Post.

"And our theory in this paper was basically that the calving front might become unstable. Once the iceberg has calved off completely, there might be a tendency for the ice front to crumble backwards."

The rift is likely to lead to an iceberg breaking off, which will remove about 10% of the ice shelf’s area pic.twitter.com/uu1KKWG0WP

— Project MIDAS (@MIDASOnIce) August 18, 2016

Just to add to Larsen C's woes, a separate study published in Nature Communications in June found that meltponds have been forming on the surface - something that's just recently been found by the thousands on the Langhovde Glacier in East Antarctica.

This will only serve to accelerate the disintegration process.

If Larsen C did end up losing all its ice, scientists have predicted that this could raise global sea levels by around 10 cm (3.9 inches).

But let's not get ahead of ourselves here. As Mooney points out, a large loss of ice from Larsen C won't necessarily be a terrible thing for the world's oceans - not immediately, at least.

"A study earlier this year in Nature Climate Change looked at ice shelves around Antarctica to determine how much area they could lose without ceasing to form their crucial function of buttressing glaciers and holding them back, and found that Larsen C actually has a lot of 'passive' ice that it can lose without major consequences," he says.

The MIDAS team isn't as optimistic, so unfortunately, we're left to wait and see when this massive chunk will break off, and what the consequences will be for life on Earth. Watch this space.