Scientists have identified a runaway supermassive black hole that appears to have been dislodged from its galactic centre by the extraordinary force of gravitational waves - ripples in space-time that were first predicted by Einstein more than a century ago.

This black hole is thought to weigh more than 1 billion Suns, and is tearing through its galaxy at speeds of roughly 7.6 million km/h (4.7 million mph). It's so far cleared an intimidating 35,000 light-years, and there's no telling where it's going to end up.

"We estimate that it took the equivalent energy of 100 million supernovae exploding simultaneously to jettison the black hole," says one of the team, Stefano Bianchi from the Roma Tre University in Italy.

While past studies have pointed to a number of cosmic anomalies in deep space as being potential 'rogue' black holes, scientists have yet to confirm any of these shadowy runaways.

But Bianchi and his team say theirs is not only an unusually strong case for a runaway black hole - it's also the first time that astronomers have found a supermassive black hole at such a large distance from its galaxy centre.

Supermassive black holes contain hundreds of millions of times the mass of our Sun. The biggest ones can even be as heavy as 10 billion Suns. There are also massive black holes, which are 100 to 100,000 times more massive than our Sun.

Massive and supermassive black holes are thought to be at the heart of every galaxy in the Universe. This looming presence is intrinsic to the existence of a galaxy - they even grow in tandem with each other - but no one's entirely sure why they always end up at the centre.

Regardless of how they got there, supermassive black holes tend to stay put in the centre of a galaxy - but physicists have hypothesised that on very rare occasions, something catastrophic can knock them free.

In this case, researchers suspect that the runaway black hole was dislodged due to a collision of two galaxies 1 to 2 billion years ago.

As Mike Wall explains over at Space.com, the central black holes of these two galaxies circled closer and closer to each other during the collision, and in the process, emitted gravitational waves - ripples in space-time that emanate from cosmic disruptions as if someone has dropped a stone in a giant pond.

"When the two central black holes finally merged, this emission stopped, and the newly created leviathan rocketed off in the opposite direction," says Wall.

In other words, some 8 billion light-years from Earth, there's a galaxy called 3C186 that could actually be the result of two galaxies merging billions of years ago.

And that means its bizarre, free-wheeling black hole could be the result of two smaller black holes eating each other, and being dislodged by the universal disruption that bursts forth from the fusion of the most massive objects known to science.

"If our theory is correct, the observations provide strong evidence that supermassive black holes can actually merge," Bianchi said in a press statement.

"There is already evidence of black hole collisions for stellar-mass black holes, but the process regulating supermassive black holes is more complex and not yet completely understood."

Seeing as black holes are impossible to see because they absorb everything, even light itself, researchers have to search for telltale signs of a black hole instead.

In this case, the Hubble Space Telescope detected a bright quasar - the energetic signature of an active black hole - some 35, 000 light-years from the centre. To put that into perspective, 1 light-year is roughly 9.5 trillion km (5.88 trillion miles).

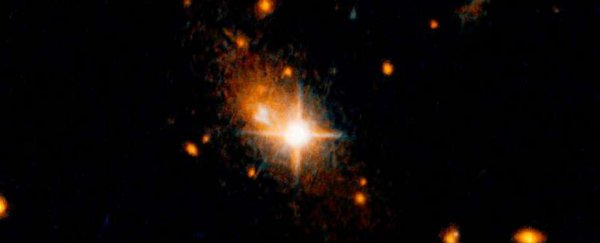

You can see the quasar in the image at the top of the page as the bright, star-like flash. Its galaxy is the orangey haze floating behind it.

Bianchi and his team have estimated that the black hole is travelling at speed of 7.6 million km/h (4.7 million mph), which means it could get from Earth to the Moon in 3 minutes.

"That's fast enough for the black hole to escape the galaxy in 20 million years and roam through the Universe forever," the team points out.

Will it one day make it to our own cosmic neighbourhood? There's no way of knowing what this violent runaway is capable of, but at least we can take comfort in the fact that we'll be long gone if or when it happens to drop by.

The research has been published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, and you can access it for free here.