Scientists in Australia have developed a technique for growing corneal cells on a thin layer of film in the lab, which can then be implanted into the eye to restore vision lost to corneal damage.

The method, which has so far been successfully demonstrated in animal trials, could have the potential to dramatically increase access to corneal transplants – which could change the lives of some 10 million people worldwide.

"We believe that our new treatment performs better than a donated cornea, and we hope to eventually use the patient's own cells, reducing the risk of rejection," says biomedical engineer Berkay Ozcelik, who led the research while at the University of Melbourne. "Further trials are required but we hope to see the treatment trialled in patients next year."

The cornea is the eye's outermost layer. To keep healthy, it needs to stay moist and transparent, but ageing, disease, and trauma can all lead to corneal damage, such as swelling, which results in vision deterioration.

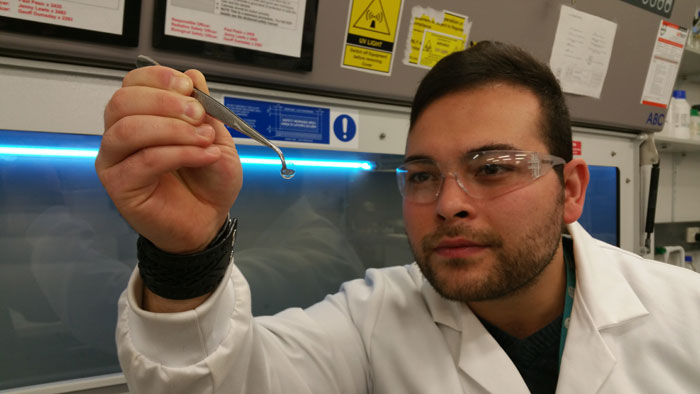

Berkay Ozcelik

Berkay Ozcelik

Corneal transplants are currently the most effective way of restoring vision lost to corneal damage, but there's a significant shortage of donor corneas. More than 47,000 cornea transplants took place in the US in 2014, but there's not enough donor tissue to satisfy the global demand.

There's also the possibility of tissue rejection from corneal donors, and the need to take steroids to fight rejection, in addition to other complications.

"The issue with donor tissue is that the whole process from handling, harvesting cells from the patients, storing and then transplanting them can have detrimental effects on the cells themselves," Ozcelik explains to Léa Surugue at the International Business Times. "There is a potential risk for disease transmission and a risk of tissue rejection, since you are transplanting from a foreign body."

The invisible film Ozcelik's team has developed could get around these problems. The technique, which has been so far tested on sheep, involves taking a sample of the subject's corneal cells, cultivating them on the synthetic film, and then returning them in greater numbers to the eye – where the regenerated cells restore moistness-pumping functions that keep the cornea healthy and clear.

"The hydrogel film we have developed allows us to grow a layer of corneal cells in the laboratory," says Berkay in a press release. "Then, we can implant that film on the inner surface of a patient's cornea, within the eye, via a very small incision."

The hydrogel film is thinner than a human hair at just 50 micrometres, and once the implanted cells have restored healthy water flowing between the cornea and the eye's interior, the film starts to degrade, disappearing in two months.

"These materials show minimal inflammation, cause no adverse issues at all and can cause regeneration of tissue, hence allowing us to use this for various applications," Ozcelik told Cheryl Hall at the ABC.

Aside from removing the risks of disease transmission or tissue rejection that come with conventional corneal transplants, another benefit of the film implant could be in cultivating healthy corneal cells for use in multiple recipients.

"The other advantage of our technique [is] even if you don't use patients' own cells, because we can regenerate and increase the number of a donor's cells in culture, we could use cornea material from one donor for maybe, say, 20 patients," Ozcelik told International Business Times.

It's not the first time we've seen scientists use these methods to restore healthy corneal functions. Earlier in the year, researchers in Japan and the UK found that human corneal cells could be implanted into the eyes of rabbits with corneal damage and restore vision.

Ozcelik now hopes to begin clinical trials with his hydrogel film next year, and while it's too early to say whether the positive results in animals can be reproduced with people, it's amazing to think of the possibilities this technique could have.

We can't wait to see where this research heads from here.