Anyone who's ever gone through the nightmare of seeing a loved one in a coma will know that sometimes all you really want is some indication of whether or not they'll actually ever wake up.

Unfortunately, every brain is different, so that's incredibly hard for doctors to predict. But research has now shown that a common test can give a pretty accurate indication of how aware a patient is - and even whether or not they're likely to wake up.

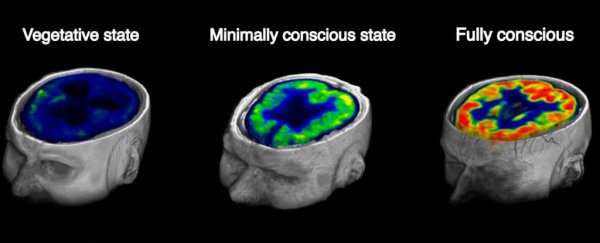

The test in question is a type of PET scan that measures how much sugar is being eaten by people's brain cells, and it's already being used in many hospitals to tell the difference between patients who are in a total coma, or those who are in a vegetative state with partial or hidden signs of awareness.

But now researchers have shown that the results can also accurately predict whether a patient will wake up.

"In nearly all cases, whole-brain energy turnover directly predicted either the current level of awareness or its subsequent recovery," said lead researcher Ron Kupers, from the University of Copenhagen and Yale University.

What the test measures is sugar metabolism, so basically how much energy brain cells are using.

That's a well established procedure, but the team has now shown that these results not only correspond closely with a patients' behavioural responses, they can also predict who will wake up from their vegetative state. "In short, our findings indicate that there is a minimal energetic requirement for sustained consciousness to arise after brain injury," explains Kupers.

To figure this out, the team mapped how much sugar was being consumed in the brains of 131 patients with brain injuries, who were all suffering either a full or partial loss of consciousness.

Using a common brain scanning technique known as FDG-PET, they measured the metabolism of neurons in these patients - and then compared those results to whether or not a patient had woken up in a year's time.

They found that those who showed less than 42 percent of normal brain activity didn't regain consciousness after a year, while those who had activity above that woke up within a year.

Overall, the test was able to accurately predict 94 percent of patients who would wake up from a vegetative state.

"The discovery of a clear metabolic boundary between the conscious and unconscious states could imply that the brain undergoes a fundamental state change at a certain level of energy turnover, in a sense that consciousness 'ignites' as brain activity reaches a certain threshold," said study co-author Johan Stender.

"We were not able to test this hypothesis directly, but it provides a very interesting direction for future research," he adds.

The team is now continuing to monitor the metabolism of injured brains over time, so they can get a better understanding of what these energy signatures mean.

The research has been peer-reviewed and published in Current Biology, but it's really important now for other scientists to repeat these tests and confirm what Kupers and his team have found.

As impressive as these results are, 131 isn't a very large sample size, so if scientists want to start using this test to predict patient outcomes in a hospital setting, they're going to need more evidence.

But it's a very promising step towards a test that might offer families of patients with brain injuries some idea of what to expect in the next year, for better or worse.

Hopefully, one day it'll also lead to better patient outcomes and treatment options - the more we know about what's going on inside these patients' brains, the better chance we have of helping them.