Scientists have developed a tiny device the size of a postage stamp that can kill 99.99 percent of bacteria in water in just 20 minutes.

Exposing contaminated water to sunlight can naturally clean it up – because UV rays blitz germs – but this distillation process usually takes up to 48 hours to complete. Instead, this new gadget harnesses a broader spectrum of the Sun's rays to speed everything up.

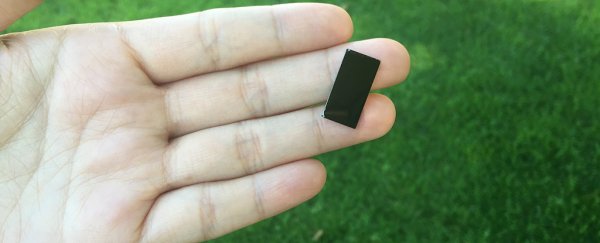

"Our device looks like a little rectangle of black glass," explains lead researcher Chong Liu from Stanford University. "We just dropped it into the water and put everything under the Sun, and the Sun did all the work."

It's the visible part of the solar spectrum, rather than UV rays, that contains most of the Sun's energy – around 50 percent for visible sunlight, compared with 4 percent for UV rays.

This visible sunlight attracts electrons in the device's coating of molybdenum disulfide (often used as an industrial lubricant), which sparks chemical reactions in the water.

Hydrogen peroxide and other disinfectants are generated from these reactions, which set about clearing the germs from the water.

Viewed under a microscope, the material is made up of many miniature walls of molybdenum disulfide, closely stacked together like a labyrinth on top of a rectangle of glass. From further out, it resembles a fingerprint.

A close-up look showing the molybdenum disulfide in purple and the copper in yellow. Credit: C. Liu et al., Nature Nanotechnology

A close-up look showing the molybdenum disulfide in purple and the copper in yellow. Credit: C. Liu et al., Nature Nanotechnology

"It's very exciting to see that by just designing a material you can achieve a good performance," says Liu. "It really works. Our intention is to solve environmental pollution problems so people can live better."

One important factor that could make the technology viable for the market is that molybdenum disulfide is cheap to produce. On top of that, money is also saved on fuel used in other purification methods, because the new device doesn't require the water to be boiled first.

The technique joins a number of other research efforts that are looking to purify water affordably for those in need. Earlier this year, we saw the cleaning properties of thin graphene sheets laid on water, and a biomaterial that pulls condensation from the air.

There's more work for the Stanford team to do before the device is ready for public use - only three strains of bacteria have been tested so far, and the coating isn't currently effective against chemical pollutants.

But while fresh and clean drinking water is something many of us take for granted, that's not the case for some 650 million people across the world –and that's something that has to change.

The research has been published in Nature Nanotechnology.