A new treatment for Huntington's disease has curbed the activity of a genetic mutation responsible for severe muscle problems and involuntary twitching for several months in a trial with mice.

The protein-based treatment is administered via a single injection, and if it continues to show promise in follow-up studies, researchers hope to test it in human trials within the next five years.

Huntington's disease is a progressive brain disorder that affects around one in every 10,000 people around the world.

Triggered by a mutation a single gene called Huntingtin, the disease damages nerve cells in the brain, and over time causes severe neurological problems such as involuntary jerking or twitching movements; difficulty walking, speaking, and swallowing; and a decline in thinking and reasoning abilities.

Patients diagnosed with the adult-onset form of Huntington disease tend to only live about 15 to 20 years after symptoms appear, and their children have a 50/50 chance of inheriting it. There is no known cure or treatment to slow the progression of the disease.

To address this, a team from Imperial College London in the UK developed a new treatment based on an engineered protein called a 'zinc finger'.

These zinc fingers are designed to attach to the DNA of mutated Huntingtin gene copies, and effectively 'block' their ability to express and produce harmful proteins that accumulate in the brain.

It's yet to be confirmed, but researchers suspect that a build-up of these proteins is what triggers the progression of the disease.

"We don't know exactly how the mutant Huntingtin gene causes the disease, so the idea is that targeting the gene expression cuts off the problem at its source - preventing it from ever having the potential to act," says lead researcher Mark Isalan.

The researchers have been investigating zinc fingers as a treatment for Huntington's disease for over a decade now, and by adjusting the composition of the protein, have managed to increase the length of the effect from a couple of weeks in 2012 to several months.

In the latest trial, the researchers treated 12 mice with Huntington's disease by giving them a single injection of zinc finger.

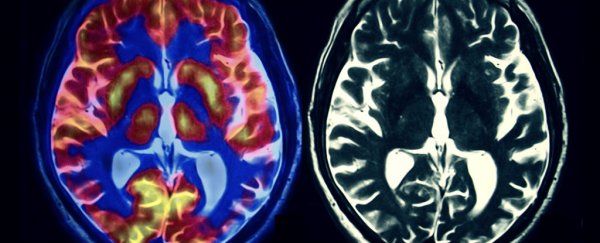

Brain scans were used to determine the progression of the disease after the treatment was administered, and the team found that, on average, 77 percent of the mutant gene expression was repressed after just three weeks.

After six weeks, 61 percent of the unwanted gene expression was still repressed, and at 12 weeks, 48 percent remained repressed.

By the 24-week mark, there was still 23 percent repression, and the researchers report that in some mice, effects were observed right up until the six-month mark after the initial injection.

There are a couple of big caveats here. First, the treatment has so far only been tested in mice, and there's no guarantee the results will be replicated in human trials.

Second, among the many mysteries surrounding Huntington's disease, one of the biggest is that we think protein build-up from mutated Huntingtin gene expression is the cause of the disease, but this has never been proved.

Third, while the researchers have shown that they can block the expression of this gene - something a separate team has achieved in both mice and monkeys using a different drug - they have yet to test if this also blocks the symptoms of the disease.

But as their 2012 trial demonstrated, mice treated with the drug were far better able to control their movements than those with no treatment, suggesting that the two are linked.

"In this study we weren't looking at how repressing the gene activity affected the symptoms of the disease, and this is obviously a critical question as well," says Isalan. "However, we have reason to be confident from our previous studies that repressing the gene does in fact significantly reduce symptoms."

The next step will be for the team to investigate these questions in follow-up animal trials, and if they can convincingly show that the treatment could halt symptoms in patients for an extended period of time, they will move on to human trials.

"If all goes well and we have further positive results, we would aim to start clinical trials within five years to see whether the treatment could be safe and effective in humans," says Isalan.

The results have been published in Molecular Neurodegeneration.