Scientists have genetically engineered tiny algae to kill up to 90 percent of cancer cells in the lab, while leaving healthy ones unharmed, and the treatment has also been shown to effectively treat tumours in mice without doing damage to the rest of the body.

Developing medicine that only attacks tumour cells and leaves the rest of the body alone is one of the biggest challenges in cancer drug therapy. Such targeted chemotherapy helps to avoid some of the devastating side-effects associated with typical chemo treatment, when all fast-dividing cells in the body are bombarded with toxic drugs – including hair follicles, nails, and bone marrow.

That's why researchers have been working on nanoparticle-based cancer drug delivery, and have been sending drug-loaded, porous silica particles into the body to target tumour cells. However, the manufacturing of these types of nanoparticles is expensive and requires industrial chemicals, such as hydrofluoric acid.

Now an international team of scientists from Australia and Germany have genetically engineered a diatom algae that can get the synthetic nanoparticle job done just as nicely.

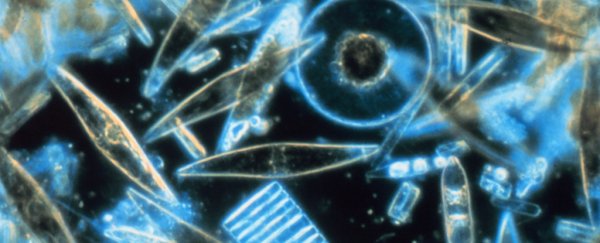

Diatoms are a large group of microscopic one-cell organisms which sport translucent cell walls composed of hydrated silicon dioxide or silica - the same type of porous material used in manufactured nanoparticle medicine. These algae are just four to six micrometres in diameter, over ten times smaller than the width of a human hair.

"By genetically engineering diatom algae - tiny, unicellular, photosynthesising algae with a skeleton made of nanoporous silica, we are able to produce an antibody-binding protein on the surface of their shells," said lead author and nanomedicine expert Nico Voelcker.

Such antibody-laden diatom nanoparticles only bind to molecules found in cancer cells, where they can release drugs. This makes it the targeted therapy researchers are looking for.

"Much attention has been paid to developing drug carriers that are natural, biocompatible and biodegradable," the authors state in their report, published in Nature Communications.

The tiny biosilica diatom algae meet these criteria, as they mostly just need water and light to grow, and can break down if left to the elements. And by choosing the right antibody, the algae nanoparticles can be easily pointed in the direction of tumour cells only.

Mr Marc Cirera

Mr Marc Cirera

The team stuffed the diatoms full of chemo drugs using a special two-step method, and then tested the nanoparticles on cancer cells both in vitro and in mice with induced neuroblastoma tumours.

Not only did the algae successfully kill roughly 90 percent of cancer cells in a dish while sparing healthy human cells, they also reduced tumour growth in mice after a single injected dose.

Furthermore, the mice also didn't have any acute tissue damage from the chemo, and the diatom biosilica safely degraded in their bodies.

The researchers believe this technique has huge potential for the future of nanomedicine and targeted cancer treatment in particular.

"Although it is still early days, this novel drug delivery system based on a biotechnologically tailored, renewable material holds a lot of potential for the therapy of solid tumours, including currently untreatable brain tumours," Voelcker said.