Just when we'd all forgotten about the second-closest planet to the Sun - what with Planet Nine taking up all our attention - an old, abandoned probe has come through with some weird data from the atmosphere of Venus.

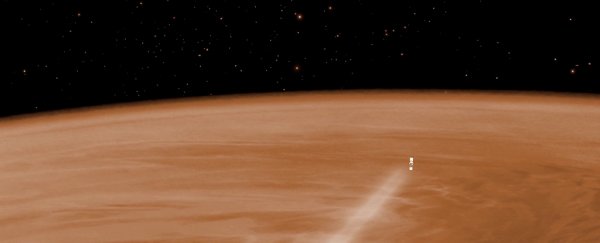

The European Space Agency's (ESA) Venus Express probe spent eight years collecting information on Venus before plunging down to the surface and out of range back in November 2014. But now we finally have the last batch of data it transmitted back to Earth before going offline, and there are some big surprises in all those recordings.

Turns out, the polar atmosphere of Venus is a whole lot colder and a lot less dense than we previously thought, and these regions are dominated by strong atmospheric waves that have never been measured on Venus before.

Maddie Stone from Gizmodo reports that the Venus Express probe found polar areas of Venus to have an average temperature of -157 degrees Celsius, which is colder than any spot on Earth, and about 70 degrees lower than was previously thought.

This is rather surprising, considering Venus's position as the hottest planet in the Solar System overall.

Not only is Venus much closer to the Sun than we are, it also has a thick, dense cloud layer that traps heat. However, Venus Express also found that the planet's atmosphere was 22 to 40 percent less dense than expected at the polar regions.

"The existing model paints an overly simplistic picture of Venus's upper atmosphere," said lead researcher, Ingo Müller-Wodarg, from the Imperial College London. "These lower densities could be at least partly due to Venus' polar vortices, which are strong wind systems sitting near the planet's poles. Atmospheric winds may be making the density structure both more complicated and more interesting!"

There's more too: the probe found these same regions to be dominated by strong atmospheric waves, which behave like ripples in a pond, except they travel vertically instead of horizontally.

These waves are thought to be key in influencing a planet's atmosphere, including the one we have here on Earth, but they've never been measured on Venus before.

What makes the discoveries even more interesting is that they were obtained using instruments that weren't intended for in-situ atmosphere observations: it was only after the launch of the Venus Express that scientists realised they could use accelerometer measurements to assess atmosphere density.

Finally, in its last moments, Venus Express proved that aerobraking – using atmospheric drag to slow down – is an effective way of making a controlled descent, and that's going to be very useful indeed when the ESA's Mars probe arrives at its destination.

"For Mars, the aerobraking phase would last longer than on Venus, for about a year, so we'd get a full dataset of Mars' atmospheric densities and how they vary with season and distance from the Sun," said Håkan Svedhem, a researcher for both the ExoMars 2016 and Venus Express missions. "This information isn't just relevant to scientists; it's crucial for engineering purposes as well."