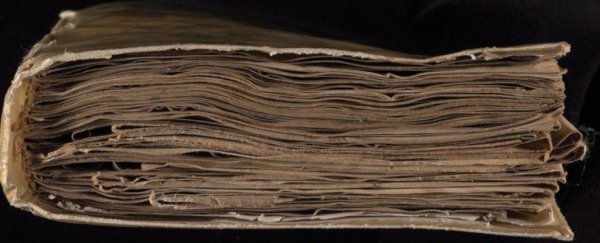

In our world, there exists an ancient and cryptic book that reads beyond human understanding. Known as the Voynich manuscript, this artefact, dating from the 15th century, has practically turned into modern legend.

Like King Arthur's 'sword in the stone', the modern 'world's most mysterious book' has attracted a host of curious readers determined to pull some sort of meaning from it.

The object was discovered in 1912 by an antiquarian named Wilfrid Voynich, and for the past century the manuscript's message has eluded all who have ever opened the cover and gone down the rabbit hole, including cryptographers, codebreakers, linguists, even computer programs.

After looking at the strange book for just two weeks, an academic in England now thinks he's got it.

"I experienced a series of 'eureka' moments whilst deciphering the code," linguist Gerard Cheshire recalls, "followed by a sense of disbelief and excitement when I realised the magnitude of the achievement, both in terms of its linguistic importance and the revelations about the origin and content of the manuscript."

It's an extraordinary claim that has been peer-reviewed and published in the journal Romance Studies. But whatever legitimacy peer-review might offer is balanced immediately by the haziness of the investigation's method.

Employing "an innovative and independent technique of thought experiment" - or as the press release puts it: "lateral thinking and ingenuity" - Cheshire believes he has found an extinct language, one that predates French, Italian, Romanian, Portuguese Spanish and Galician.

Cheshire is convinced that the text is written in a perfectly normal proto-Roman language, an example that has been lost to history, and is remarkable not for its cleverly-written code, but rather for being so very commonplace.

Translating parts of the text, he says it discusses herbal remedies, bathing, astrological readings and the female body. He even claims to know who wrote it: a Dominican nun compiled this as a reference for the "female royal court" of Maria of Castile, Queen of Aragon.

The image below, for instance, is said to depict two women dealing with five children in a bath, exclaiming phrases that supposedly resemble Catalan, Portuguese and Romanian words, such as "too noisy", "silly/foolish", "slippery" and even "losing patience", which could, the author suggests, be the root of the French phrase 'oh là là', or 'oh dear'.

(Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

(Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

It's easy to tell when a legendary sword has been extracted, but in this case, how do we know that Cheshire is wielding the right explanation? Some scholars are approaching these latest claims with fierce skepticism.

Speaking to Jennifer Ouellette at Ars Technica, Lisa Fagin Davis, who is the executive director of the Medieval Academy of America, was scathing in her assessment of Cheshire's claims.

"As with most would-be Voynich interpreters, the logic of this proposal is circular and aspirational: he starts with a theory about what a particular series of glyphs might mean, usually because of the word's proximity to an image that he believes he can interpret," she says.

"In addition, the fundamental underlying argument - that there is such a thing as one 'proto-Romance language' - is completely unsubstantiated and at odds with paleolinguistics."

This is far from the first time an interpretation of the Voynich Manuscript has appeared on shaky ground. Over the years, many similar claims have surfaced, some more believable than others, but most of them debunked in the end.

Last year, a peer-reviewed computer algorithm found that the language in the 200-page text most resembled Hebrew and not Romance languages.

In 2017, a history researcher and television writer named Nicholas Gibbs made headlines when he claimed the text was a women's health manual with a bunch of Latin abbreviations.

Providing a mere two lines of translation as proof, his ideas were soon shot down, with several experts arguing the topic of women's health had already been well-established.

And maybe, just maybe, the joke is on all of us. A few years ago, a new research paper found evidence that the whole thing may simply be an elaborate hoax.

Spending more than a decade of research on the text, the lead author, Gordon Rugg of Keele University, argues that the manuscript's elaborate 'language' would have been easy to fake if the author knew a few simple coding techniques.

In other words, we may have spent all this time tugging on the sword, only to realise it's super-glued into the rock.

This study has been published in the journal Romance Studies.