Scientists have discovered two partial human skulls in central China that they say could potentially belong to an unknown archaic human species.

The skulls are 105,000 to 125,000 years old, and they contain a unique mix of modern human and Neanderthal features. Excitingly, they could be the key to filling in some of the missing pieces of the human family tree in east Asia.

Without DNA analysis, the team is reluctant to speculate about the owners of the skulls, but they've suggested that the remains could potentially represent a new, archaic human species that we haven't previously stumbled upon.

That's not as unlikely as it sounds - there are hints in our genetic records that there are still significant missing ancestors on our family tree we're yet to uncover.

But there's also another possibility.

Something the researchers didn't speculate on in their paper is that the skulls could be rare physical evidence of the Denisovans, a mysterious cousin of Neanderthals that are thought to have lived between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago.

It's estimated that modern humans living in China contain around 0.1 percent Denisovan DNA, which suggests that at some point modern humans lived alongside and bred with the Denisovans.

But other than a lone finger bone and a couple of teeth found in a Siberian cave in 2008, we have very little trace of them in the fossil record, so it's been hard to piece the story together.

While the team didn't mention Denisovans in their research, it's something other researchers have jumped on.

"Everyone else would wonder whether these might be Denisovans," paleoanthropologist Chris Stringer from the Natural History Museum in London, who wasn't involved in the research, told Ann Gibbons over at Science Magazine.

"This would be the combination that one would expect based on the ancient DNA analysis of Denisovans, who were closely related to Neanderthals," Neanderthal expert Katerina Harvati from the University of Tübingen in Germany, also unrelated to the discovery, told The Washington Post.

Without further research - DNA evidence in particular - it's impossible to tell which of these possibilities are more likely: if these skulls belong to a brand new human species, or are rare traces of Denisovans in east Asia. It's also impossible to rule out other possibilities.

But the discovery has the scientific world pretty pumped.

"It is a very exciting discovery," said Harvati. "Especially because the human fossil record from east Asia has been not only fragmentary but also difficult to date."

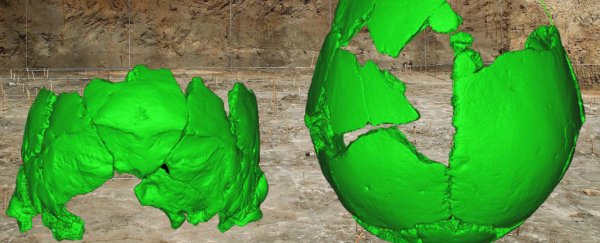

The two partial skulls, which are pictured at the top of the page, were found at the Lingjing site in Xuchang, in central China's Henan province, back in 2007 and 2014.

While scientists are beginning to piece together a clearer idea of how human ancestors spread out of Africa, once they reached east Asia the picture has become more blurry.

Which is why the find is so important - these skulls could help us explain how our early ancestors eventually went on to become the modern humans we see living in eastern Eurasia today.

For now, the team has simply labelled the two fossilised skulls as belonging to "archaic Homo" - no DNA has been able to be extracted from the incredibly old samples as yet, so any further identification is impossible.

But what we do know is the physical appearance of the skulls is like nothing we've seen in the human fossil record up until now, representing what the researchers call a "mosaic" of human and Neanderthal features.

Like modern humans, the skulls have modest brow lines, lightly built cranial vaults, and large brain capacity.

But they also have the same semicircular ear canals, and enlarged section at the back of the skull, as Neanderthals.

And there are traits of early eastern Eurasian humans, too, such as a low and broad braincase that rounds onto the inferior skull.

The large brain spans rule out the possibility that the skulls could have been Homo erectus or other known hominid species, the researchers write in Science.

But it's still not clear exactly what they were.

Reluctant to speculate on the Denisovan possibility, one of the researchers, Xiujie Wu from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, told Science Magazine that the fossils could represent "a kind of unknown or new archaic human that survived on in East Asia to 100,000 years ago".

The team suggests this unidentified new species might have been part of a population in eastern Asia that lived alongside and interacted with Neanderthals and modern humans, and passed down local traits through the generations.

The site that the skulls were found at was thought to be inhabited some 105,000 to 125,000 years ago, during the Pleistocene epoch, when that part of the world was covered in large ice sheets.

According to other discoveries at the site, the owners of the skulls were good hunters who had fashioned stone blades out of quartz. There were also the bones of ancient horses and cattle, as well as now-extinct woolly rhinoceros and giant deer, strewn around the site.

Regardless of who these skulls belonged to, the mishmash of features do tell us one important thing - they suggest that there was a continual and connected population that lived across Eurasia, rather than individual isolated groups.

"The features of these fossils reinforce a pattern of regional population continuity in eastern Eurasia, combined with shared long-terms trends in human biology and populational connections across Eurasia," said lead researchers Erik Trinkaus, from Washington University in St. Louis, in a statement.

"They reinforce the unity and dynamic nature of human evolution leading up to modern human emergence."

Time will tell whether the team might be able to successfully extract DNA from the skulls with further attempts. Without that genetic material, it will be impossible to say for sure what species these skulls belonged to. But it's possible that further excavation at the site might yield more clues.

And even without a definitive identification on the mysterious human species, the discovery still has a lot to teach us.

"China is rewriting the story of human evolution," paleoanthropologist María Martinón-Torres from the University College London told Gibbons.

"I find this tremendously exciting!"

The research has been published in Science.