How's your throwing arm? Probably not as good as the ancient supervolcanoes in Australia, which scientists have discovered had enough explosive power to fling rocks to the other side of the country – more than 1,400 miles (2,253 kilometres) away.

The research is helping us understand more about how the continent, and its unique landscapes, once formed.

It's long been known that the east coast of Australia is home to ancient supervolcanoes, but what wasn't clear until now was what kind of role they played in forming the country.

To figure this out, a team from Curtin University in Western Australia analysed the age and composition of geological material across the west side of the country.

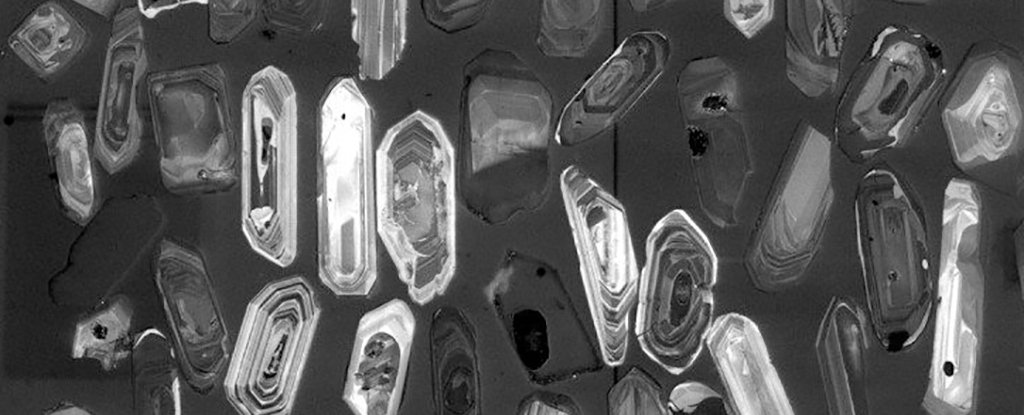

The study revealed sand-sized zircon crystals that didn't match up with any of the typical rock composition in Western Australia – but that did reflect the volcanic rock of the Whitsundays area in north-east Australia, in terms of both age and geochemicals.

Milo Barham/Curtin University

Milo Barham/Curtin University

That suggests that the giant volcanoes that were once dotted the north-eastern coast belched rocks far and wide – including all the way to the other side of the country. Until now, the local craters and solidified lava flows were all researchers had to go on when estimating the size of these ancient eruptions.

"Such distal projection of a unique volcanic mineral population demonstrates that super-eruptions were occurring in eastern Australia approximately 106 million years ago, during the break-up of the supercontinent Gondwana," said lead researcher, Milo Barham.

Based on an analysis of the arrangement of land masses and atmospheric conditions at the time, it looks like the super-eruptions happened during the southern hemisphere's winter, when strong winds from the east would have helped to push the volcanic rock westwards, according to Barham.

If the scientists' hypothesis is right, the super-eruptions would've been tens to hundreds of times more powerful than any in recorded history, reports Alice Klein for New Scientist.

Were such an eruption to happen today in Queensland, it would be heard all the way over in Perth.

Being able to get insight into eruptions of this type is important to scientists studying the changes that have happened to Earth's climate over time – an eruption that would have been powerful enough to blast rocks thousands of kilometres would most likely have had a significant cooling effect as well.

But the research will also help the team trace the evolution of different species, and help scientists to predict when and if eruptions of this strength will happen again.

Because it's not just ancient supervolcanoes that can toss material this far. The Eyjafjallajökull eruptions in 2010 were much smaller but are the most recent modern example of how debris and ash can be blown across huge distances – with the ash cloud spreading thousands of kilometres and disrupting air travel around the world.

The biggest super-eruption on record, meanwhile, came from the Toba volcano in Indonesia some 75,000 years ago.

In that case, sand-sized particles were blown over a 1,700-mile (2,735-km) radius, as shown by ash layers found deep below the ocean, but experts are divided on how much of an impact the blast had on the planet's climate.

Peering back this far into history isn't easy, but the more data scientists have access to, the better they can piece together what happened.

"The incomplete nature of geological sequences means that recognising these earth-shattering volcanic events is difficult in deeper geological time, millions to billions of years ago," said Barham.

The research has now been published in Geology.