Since NASA's Dawn spacecraft captured images of eerie bright spots on the surface of the dwarf planet Ceres back in March, scientists and the public alike have been speculating over what could be creating them. Volcanoes? Geysers? Ice deposits? With "other" topping a NASA poll asking for the most likely possibility, we all had sit back and be as clueless as each other until Dawn got the opportunity to go in for another look.

But now we've finally got our hands on the data from Dawn's most recent fly-by, and separate teams of researchers have come up with a couple of fascinating insights: the bright material that gives these spots their distinctive shine looks to be some kind of icy salt, and it contains deposits of ammonia-rich clays, which hints at how Ceres formed.

Pocked with more than 130 of these bright spots, most of which are nearby impact craters, Ceres appears to harbour deposits of a type of pale white magnesium sulphate called hexahydrite. Similar to Epsom salt, hexahydrite forms fibrous, flaky layers on the surface of rocks, and while rarely seen on Earth, it can be found around the Cave of Saint Ignatius in Manresa, Spain.

Based on observations from Dawn's framing camera, the researchers suspect that the salt-rich spots on Ceres formed back when water-ice sublimated below the surface thanks to asteroid impacts. "The simplest scenario is that the sublimation process of water ice starts after a mixture of ice and salt minerals is exposed by an impact, which penetrates the insulating dark upper crust," the researchers write in their Nature paper.

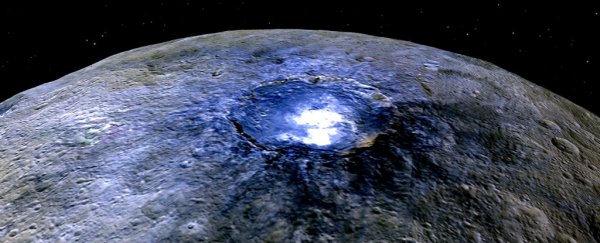

Easily visible against the typically dark surface of the dwarf planet, these bright spots give off a wide range of brightness, with some of them reflecting up to 50 percent of the sunlight. The brightest material has been located in the Occator crater, which stretches to about 90 kilometres (60 miles) in diameter and features strange dark streaks running through its 0.5-km-deep (0.3 miles) cavity.

Occator appears to be among the youngest features on Ceres, with researchers estimating that it's about 78 million years old. The team, led by Andreas Nathues from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany, is now investigating a strange haze that appears near the base of the crater only at certain times of day.

A separate team led by Maria Cristina De Sanctis from Italy's National Institute of Astrophysics has announced the detection of ammonia-rich clays in the surface material of Ceres. Using data from Dawn's visible and infrared mapping spectrometer, the researchers describe how ammonia ice would evaporate in the atmosphere of Ceres, but if chemically bound to other minerals, it could remain in a stable form on the surface.

"The presence of ammoniated compounds raises the possibility that Ceres did not originate in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, where it currently resides, but instead might have formed in the outer Solar System," says NASA. "Another idea is that Ceres formed close to its present position, incorporating materials that drifted in from the outer solar system - near the orbit of Neptune, where nitrogen ices are thermally stable."

"The results are quite unexpected," De Sanctis told Maddie Stone at Gizmodo. "We are now analysing the data taken at higher resolution that could reveal more details about the variegation in composition of the surface."

The results have been published in a separate paper in Nature.