In February 1987, the sky lit up. In the Large Magellanic Cloud, 167,644 light-years away, astronomers watched as a massive star died in a spectacular supernova, the closest to Earth in hundreds of years.

But when the fireworks died down, something was missing. There was no sign of the neutron star that should have been left behind.

Now, 33 years later, astronomers have finally caught a glimpse of that dead star, gleaming out from a thick cloud of obscuring dust at the centre of the supernova remnant - the glowing debris of its own stellar viscera.

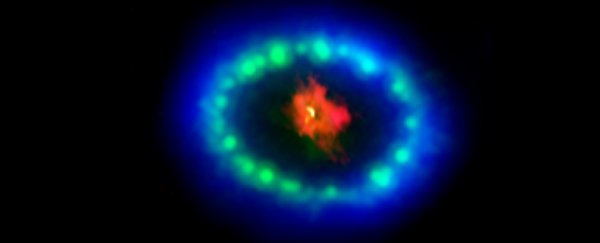

Multi-wavelength images of SN1987A, with the yellow blob in the centre of the composite image suggested to be the neutron star NS 1987A. (ALMA [ESO/NAOJ/NRAO], P. Cigan and R. Indebetouw; NRAO/AUI/NSF, B. Saxton; NASA/ESA)

There are several types of supernovae, depending on the type of star dying. Those that produce a neutron star - Type II supernovae - start with a star between eight and 30 times the mass of the Sun, which becomes increasingly unstable as it runs out of elements to support nuclear fusion.

Finally, it explodes, ejecting its outer material and spewing light and neutrinos out across space, while the core collapses down into a neutron star.

In the case of 1987's supernova, everything occurred just as expected. An old blue supergiant star called Sanduleak -69 202, about 20 times the mass of the Sun, went kaboom in a spectacular lightshow - so bright it was visible to the naked eye - corresponding with a neutrino shower detected here on Earth.

The event left behind a glowing supernova remnant named SN 1987A. But at the centre, astronomers could find no trace of the expected newborn neutron star.

Then, in November of last year, a team of researchers led by Phil Cigan of Cardiff University in the UK announced that they had finally found a hot, bright blob in the remnant's core using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile. It was, they said, consistent with a neutron star shrouded by a thick cloud of dust.

"We were very surprised to see this warm blob made by a thick cloud of dust in the supernova remnant. There has to be something in the cloud that has heated up the dust and which makes it shine. That's why we suggested that there is a neutron star hiding inside the dust cloud," explained astrophysicist Mikako Matsuura of Cardiff University.

But there was still a problem. Whatever it was glowing inside the blob, it looked like it might perhaps be too bright to be a neutron star.

That's where a team led by astrophysicist Dany Page of the National Autonomous University of Mexico comes in. Page had been a PhD student when Sanduleak -69 202 went kablooey, and he has been studying SN 1987A ever since.

In a new paper, Page and his team have theoretically demonstrated that the glowy blob can indeed be a neutron star. Its brightness is consistent with thermal emission from a very young neutron star - in other words, it's still really, really hot from the supernova explosion. They have named the neutron star NS 1987A.

"In spite of the supreme complexity of a supernova explosion and the extreme conditions reigning in the interior of a neutron star, the detection of a warm blob of dust is a confirmation of several predictions," Page said.

The heat - around 5 million degrees Celsius (9 million degrees Fahrenheit) - is one of those predictions. Another is the star's location. It's not exactly at the centre of the supernova, but travelling away from it at a velocity of up to 700 kilometres per second (435 miles per second).

This is not unusual at all - if a supernova explosion is uneven, it can boot the collapsed stellar core out across the galaxy, at absolutely insane speeds.

The team also compared the observations with other possible scenarios, such as the radioactive decay of isotopes. They also examined the fit for a pulsar - a type of rapidly spinning, pulsing neutron star - or a black hole. None of these explanations fit the data as well as a normal neutron star.

According to the team's analysis, NS 1987A would be around 25 kilometres across, and around 1.38 times the mass of the Sun - all extremely normal for a neutron star.

But it's also the youngest neutron star we've ever seen - the next youngest is inside supernova remnant Cassiopeia A, which is 11,000 light-years away, and which exploded in the 17th century - meaning it can offer invaluable insights into this metamorphic stage of stellar evolution.

"The neutron star behaves exactly like we expected," said astronomer James Lattimer of Stony Brook University.

"Those neutrinos suggested that a black hole never formed, and moreover it seems difficult for a black hole to explain the observed brightness of the blob. We compared all possibilities and concluded that a hot neutron star is the most likely explanation."

Because the putative neutron star is still shrouded in dust, the direct observation that would confirm this finding is, at the moment, impossible. Astronomers are going to be watching it for decades to come to see what emerges from that cloudy chrysalis.

The research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal.