In the beginning, there was darkness. And then, after hundreds of millions of years, light from primitive suns spilled freely across the Universe.

What caused the lifting of this veil, however, has been something of a mystery. Now astronomers have developed a new hypothesis to explain how that primeval fog was pushed aside, allowing light from the massive stars to radiate through space.

Researchers from the University of Iowa and the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics hit on this new idea thanks to observations of a rather unusual galaxy just 600 million light years away.

Tol 1247-232 is one of only three nearby galaxies that emit light in the UV spectrum. More specifically, they emit frequencies of UV light in what's called the Lyman series.

Lyman series radiation is defined as light with just the right amount of energy to kick the electron off hydrogen, making it an important form of ionising radiation. Thick clouds of dust and gas usually get in the way of this UV radiation, making it hard for those frequencies to be detected directly here on Earth.

For this light to get to us, Tol 1247-232 must have something going on that most other galaxies don't. A twinkling light seems to have provided a clue.

"Stars don't have changes in brightness," says lead researcher Philip Kaaret from the University of Iowa.

"Our Sun is a good example of that. To change in brightness, you have to be a small object, and that really narrows it down to a black hole."

Along with one of the other nearby UV-shining galaxies, Haro 11, Tol 1247-232 shines quite brightly with X-rays.

"The observations show the presence of very bright X-ray sources that are likely accreting black holes," says Kaaret.

Could these rather powerful black holes have pushed aside enough dust to let the galaxy's Lyman radiation shine through?

The problem is black holes are more like cosmic dust-busters that polish a small gap in their immediate surroundings, not leaf blowers that blow things around, cleaning out an entire galactic yard.

So astronomers still aren't entirely sure how a black hole might blow instead of suck, though it's possible its rotation might have something to do with it.

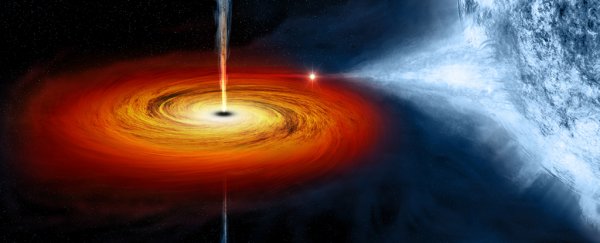

As its immense gravity pulls material in closer, the black hole's spin picks up speed, increasing the amount of kinetic energy in the swirling vortex of matter skimming its gravitational horizon.

Not only does this produce the waxing and waning shine of X-rays astronomers use to spot its position, the bursts of energy are thought to also squirt out jets of material.

"As matter falls into a black hole, it starts to spin and the rapid rotation pushes some fraction of the matter out," Kaaret says. "They're producing these strong winds that could be opening an escape route or ultraviolet light."

As well as potentially explaining the characteristics of Lyman-emitting galaxies such as Tol 1247-232, it could also solve a bigger mystery concerning a period in our early Universe called the Epoch of Reionisation.

Soon after the Big Bang, as space expanded, all of those packets of light radiation bouncing around cooled steadily into a dense mist of sub-atomic particles. With more room those particles coalesced into things like protons and electrons, and eventually into atoms of hydrogen.

Gravity then started to pull those atoms together into the first stars, which emitted radiation. But the Universe was still packed full of plenty of hydrogen, which prevented light from travelling very far.

This is called the Dark Ages of the Universe, and like the name suggests, it didn't leave much of a light echo in the distant reaches of space to tell us what went on.

Anywhere between 100 million and a billion years after the Big Bang, the Lyman radiation from the bigger stars began to turn those hydrogen atoms back into ions as the UV light knocked off electrons. Just how the Lyman radiation pierced the dense, dark fog has yet to have a satisfactory answer.

But Tol 1247-232 could be shining a light on the problem, suggesting the first big, black holes might have played a role in clearing the way for ionising radiation to shine.

"Thus, black holes may have helped make the Universe transparent," says Kaaret.

This research was published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.