Nearly 2,000 years ago, the first human-documented supernova was observed by ancient Chinese astronomers, who witnessed a bright "guest star" lighting up the night sky in 185 AD.

A couple of millennia later, scientists have proposed various explanations for what gave rise to the supernova remnant RCW 86, but now a team of astrophysicists think they've pinned it down: the supernova was caused by one half of an exploding binary star system, which blasted its stellar partner with a flood of heavy elements, including calcium.

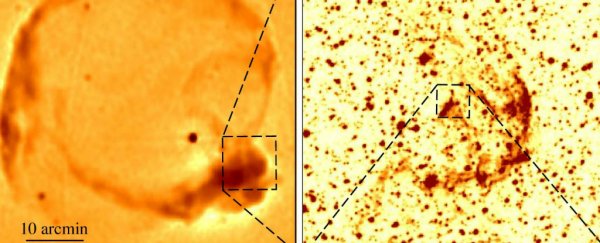

In a previous study, researcher Vasilii Gvaramadze from Lomonosov Moscow State University in Russia had hypothesised that the pear-shaped appearance of RCW 86 (seen below) might be due to a supernova explosion near the edge of a 'bubble' blown by the wind of a moving massive star – what's called a stellar wind bubble.

Using data from the Chandra X-ray Observatory, he was able to detect a candidate neutron star, called [GV2003] N, which was thought to be the neutron star remaining after the supernova that produced RCW 86.

X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO & ESA; Infrared: NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Williams (NCSU)

X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO & ESA; Infrared: NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Williams (NCSU)

Supernovae can occur when a star runs out of its nuclear fuel towards the end of its life – as this happens, the star starts to consume its own core, leading to a huge explosion when the core collapses, and resulting in either a supermassive black hole or a neutron star.

In this case, it was thought that the supernova produced the neutron star [GV2003] N, but there was only one problem. Neutron stars are supposed to be very dim, but readings taken in 2010 showed that the star at the position of [GV2003] N was in fact very bright.

"In order to determine the nature of the optical star at the position of [GV2003] N, we obtained its images using [the] 7-channel optical/near-infrared imager GROND at the 2.2-metre telescope of the European Southern Observatory (ESO)," says Gvaramadze.

The observations introduced another puzzle. While the light shone by the star indicated it was a G-type star like our Sun, it also seemed to produce too many X-rays for a G-type.

The logical conclusion? We weren't looking at one star, after all.

"[S]ince the X-ray luminosity of the G star should be significantly less than [w]hat was measured for [GV2003] N, we have come to a conclusion that it is a binary system composed of a neutron star (visible in X-rays as [GV2003] N) and a G star, visible in optical wavelengths," says Gvaramadze.

Vasilii Gvaramadze

Vasilii Gvaramadze

This means the supernova could have been a dramatic stage in the evolution of this binary system, in which one of the stars exploded in a supernova event, polluting its companion with a range of heavy elements – and leaving its atmosphere with six times as much calcium as it should otherwise have.

To verify their hypothesis, the team checked observation data taken with the ESO's Very Large Telescope in Chile. The measurements confirmed [GV2003] N's was a binary system, with the two stars orbiting one another about once per month.

The researchers acknowledge that there's still a lot we don't know about this star system, but it gives us a great opportunity to find out more about these rare calcium-rich supernovae – about which little is currently understood by scientists.

To that end, Gvaramadze and his team intend to continue studying [GV2003] N, to see what else we can learn about it.

"We are going to determine orbital parameters of the binary system, estimate the initial and final masses of the supernova progenitor, and the kick velocity obtained by the neutron star at birth," says Gvaramadze.

"Moreover, we are also going to measure abundances of additional elements in the G star atmosphere. The obtained information could be crucially important for understanding the nature of the calcium-rich supernovae."

The findings are reported in Nature Astronomy.