Doctors in a Canadian intensive care unit stumbled on a very strange case last year - when life support was turned off for four terminal patients, one of them showed persistent brain activity even after they were declared clinically dead.

For more than 10 minutes after doctors confirmed death through a range of observations, including the absence of a pulse and unreactive pupils, the patient appeared to experience the same kind of brain waves (delta wave bursts) we get during deep sleep.

And it's an entirely different phenomenon to the sudden 'death wave' that's been observed in rats following decapitation.

"In one patient, single delta wave bursts persisted following the cessation of both the cardiac rhythm and arterial blood pressure (ABP)," the team from the University of Western Ontario in Canada reported in March 2017.

They also found that death could be a unique experience for each individual, noting that across the four patients, the frontal electroencephalographic (EEG) recordings of their brain activity displayed few similarities both before and after they were declared dead.

"There was a significant difference in EEG amplitude between the 30-minute period before and the 5-minute period following ABP cessation for the group," the researchers explained.

Before we get into the actual findings, the researchers are being very cautious about the implications, saying it's far too early to be talking about what this could mean for our post-death experience, especially considering their sample size is one.

In the absence of any biological explanation for how brain activity could possibly continue several minutes after the heart has stopped beating, the researchers said the scan could be the result of some kind of error at the time of recording.

But they were at a loss to explain what that error could be, as the medical equipment showed no signs of malfunction, meaning the source of the anomaly cannot be confirmed - biologically or otherwise.

"It is difficult to posit a physiological basis for this EEG activity given that it occurs after a prolonged loss of circulation," the researchers wrote.

"These waveform bursts could, therefore, be artefactual [human error] in nature, although an artefactual source could not be identified."

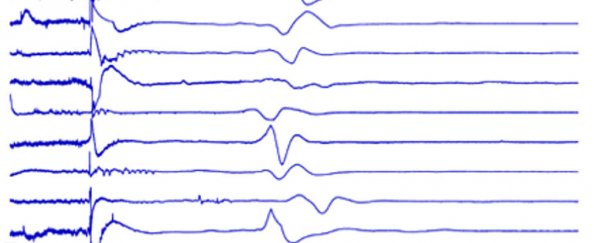

You can see the brain scans of the four terminal patients below, showing the moment of clinical death at Time 0, or when the heart had stopped a few minutes after life support had been turned off:

Norton et al. (2017)

Norton et al. (2017)

The yellow brain activity is what we're looking for in these scans (view a larger version here), and you can see in three of the four patients, this activity faded away before the heart stopped beating - as much as 10 minutes before clinical death, in the case of patient #2.

But for some reason, patient #4 shows evidence of delta wave bursts for 10 minutes and 38 seconds after their heart had stopped.

The researchers also investigated if a phenomenon known as 'death waves' occurred in the patients - in 2011, a separate team observed a burst of brain activity in rat brains about 1 minute after decapitation, suggesting that the brain and the heart have different moments of expiration.

"It seems that the massive wave which can be recorded approximately 1 minute after decapitation reflects the ultimate border between life and death," researchers from Radboud University in the Netherlands reported at the time.

Bas-Jan Zandt et al. (2011)

Bas-Jan Zandt et al. (2011)

When the Canadian team looked for this phenomenon in their human patients, they came up empty.

"We did not observe a delta wave within 1 minute following cardiac arrest in any of our four patients," they reported.

If all of this feels frustratingly inconsequential, welcome to the strange and incredibly niche field of necroneuroscience, where no one really knows what's actually going on.

But what we do know is that very strange things can happen at the moment of death - and afterwards - with a pair of studies from 2016 finding that more than 1,000 genes were still functioning several days after death in human cadavers.

And it wasn't like they were taking longer than everything else to sputter out - they actually increased their activity following the moment of clinical death.

The big takeaway from studies like these isn't that we understand more about the post-death experience now than we did before, because the observations remain inconclusive and without biological explanation.

But what they do show is that we've got so much to figure out when it comes to the process of death, and how we - and other animals - actually experience it, from our bodies to our brains.

The research has been published in The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences.

A version of this article was first published in March 2017.