Scientists have discovered that brain cells that were once considered to be simple place-holders for neurons could actually play an important role in helping to regulate our circadian behaviour.

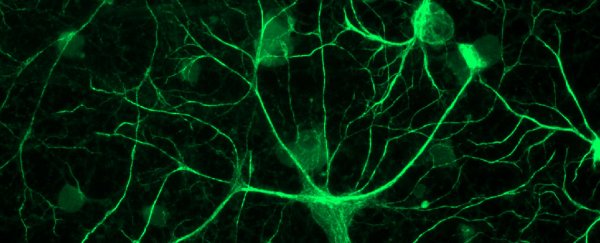

Astrocytes are a kind of glial cell – the support cells that are often called the glue of the nervous system, as they provide structure and protection for neurons. But a new study shows that astrocytes aren't just gap-fillers, and may be crucial for keeping time in our inner body clock.

Scientific consensus has long regarded our internal clock as being controlled by the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN), a brain region in the hypothalamus made up of around 20,000 neurons. But there's about 6,000 star-shaped astrocyte cells in the same area, the exact function of which has never been fully explained.

Now, a team from Washington University in St. Louis has figured out how to independently control astrocytes in mice – and by altering the astrocytes, the scientists were able to slow down the animals' sense of time.

"We had no idea they would be that influential," says one of the researchers, Matt Tso.

It was once thought the suprachiasmatic nuclei was the only part of the brain that regulated circadian rhythms, but scientists now understand that cells throughout the body all have their own circadian clocks – including the cells that make up our lungs, heart, liver, and everything else.

In 2005, one of the team, neuroscientist Erik Herzog, helped figure out that astrocytes also include these clock genes.

By isolating the brain cells from rats and coupling them with a bioluminescent protein, Herzog's team showed that they glowed rhythmically – evidence that they were capable of keeping time like other cells.

It took more than a decade for the researchers to figure out how to measure the same astrocyte behaviour in a living specimen, by using CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing to delete a clock gene called Bmal1 in the astrocytes of mice.

Left to their own devices, mice have circadian clocks that last for approximately 23.7 hours. We know this because mice in constant darkness will start running on a wheel every 23.7 hours, and usually don't miss their time slot by more than 10 minutes.

Humans also miss the 24-hour mark slightly – a Harvard University study in 1999 found that our internal clocks run a tad overlong, on a daily cycle of 24 hours, 11 minutes.

But even though Herzog had demonstrated in 2005 that astrocytes were involved in keeping time, the team didn't necessarily expect mice without Bmal1 to be affected, because most research surrounding the suprachiasmatic nuclei has demonstrated the controlling effect of neurons, not astrocytes.

"When we deleted the gene in the astrocytes, we had good reason to predict the rhythm would remain unchanged," says Tso.

"When people deleted this clock gene in neurons, the animals completely lost rhythm, which suggests that the neurons are necessary to sustain a daily rhythm."

But, to the researchers' surprise, deleting the clock gene in the astrocytes saw the mouse internal clocks run slower – beginning their daily run about 1 hour later than usual.

In another experiment, the team studied mice with a mutation that caused their circadian clocks to run fast. By repairing this gene in the animals' astrocytes – but not fixing the defect in their neurons – they weren't sure what the affect would be.

"We expected the SCN to follow the neurons' pace," says Tso. "There are 10 times more neurons in the SCN than astrocytes. Why would the behaviour follow the astrocytes?"

With the mutation fixed in the animals' astrocytes, the mouse began their running routine 2 hours later than mice that hadn't had the mutation repaired (in either astrocytes or neurons).

"[These results] suggests that the astrocytes are somehow talking to the neurons to dictate rhythms in the brain, and in behaviour," Herzog told Diana Kwon at The Scientist.

While the researchers acknowledge that they don't fully understand the extent to which astrocytes control circadian behaviour, it's clear something powerful is going on.

Of course, we can't guarantee yet whether astrocytes in humans are regulating body clocks in the same way, but that's something that later studies may be able to confirm.

We'll have to wait to see the results of future research to know more, but until then, one thing's for sure – these brain cells are definitely there for a lot more than just neuron padding.

The findings are reported in Current Biology.