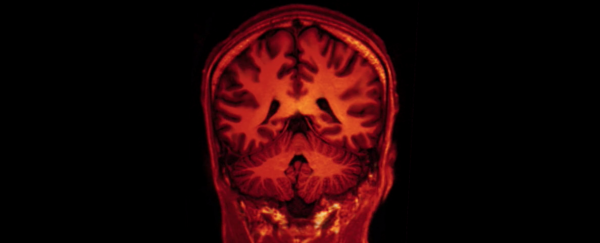

New research has put to rest a decades-old mystery by showing that prolonged depression causes brain damage, not the other way around.

An international team of scientists found that depression can lead to reversible shrinking in the hippocampus - the region of the brain responsible for forming new memories. And while they believe that this damage causes further emotional and behavioural changes, the results suggest that it's the depression that comes first.

"I think this resolves for good the issue that persistent experiences of depression hurt the brain," one of the researchers, Ian Hickie from the University of Sydney in Australia, told Sasha Petrova over at The Conversation.

Scientists have known for decades that shrinking in the hippocampus plays a role in depression, but the results on which came first had been inconclusive.

The new study looked at MRI brain scans of more than 9,000 people, and found that people who had depression before the age of 21 and those who had experienced recurrent depressive episodes both had significantly smaller hippocampus volumes than people who never had repeated incidences of depression.

"Those who have only ever had one episode do not have a smaller hippocampus, so it's not a predisposing factor but a consequence of the illness state," said Hickie. The results also suggest that the damage actually worsens depressive symptoms.

"We've seen in a lot of other animal experiments that when you shrink the hippocampus, you don't just change memory, you change all sorts of other behaviours associated with that – so shrinkage is associated with a loss of function," explained Hickie. "It puts the emphasis then on early identification of the more severe persistent or recurrent cases. Importantly, in early identification systems you have to stick with those in who it persists or is recurrent, because they're the ones who will be most harmed from a brain point of view."

While there are no immediate clinical applications of the work, the research will help scientists to better understand the jigsaw puzzle that is depression, and hopefully use that knowledge to develop better treatments for the condition.

"This study confirms - in a very large sample - a finding that's been reported on quite a few occasions," said Philip Mitchell, a psychiatrist at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Australia, who wasn't involved in the research. "It's interesting that none of the other subcortical areas of the brain have come up as consistently, so it also confirms that the hippocampus is particularly vulnerable to depression."

The most promising aspects of the research is that the physical damage caused by depression is reversible. "The hippocampus is one of the most important regenerative areas of the brain," added Hickie.

The research has been published in Molecular Psychiatry.