In the local people's tongue, her name means 'sunrise girl-child', and even though she only lived for six fleeting weeks, she's already told scientists more than we ever knew about the very first Native Americans.

Sunrise girl-child ("Xach'itee'aanenh T'eede Gaay") lived some 11,500 years ago in what is now called Alaska, and her ancient DNA reveals not only the origins of Native American society, but reminds the world of a whole population of people forgotten by history millennia ago.

"We didn't know this population existed," says anthropologist Ben Potter from the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

"It would be difficult to overstate the importance of this newly revealed people to our understanding of how ancient populations came to inhabit the Americas."

(Ben Potter)

(Ben Potter)

It's widely thought that the first American settlers crossed over into Alaska from Siberia via the Bering Land Bridge, which once linked up Asia and North America – although scientists are ever debating how these ancient travellers made their journey.

What's less clear is who these people were, how many groups made the trip, and how they then settled the new continent under their feet. That's where sunrise girl-child comes in.

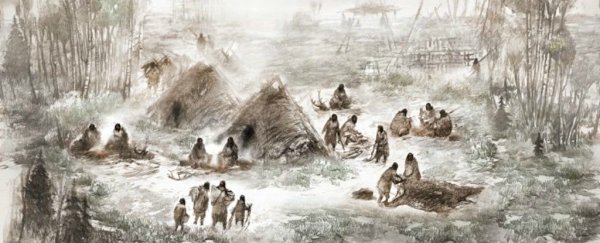

Her remains, and those of another ancient infant known as "Yełkaanenh T'eede Gaay" (dawn twilight girl-child), were found by Potter and fellow researchers at an Interior Alaska archaeological site called Upward Sun River during excavations in 2013.

In a new study published this week, the team reports that a genetic analysis of sunrise girl-child's DNA shows she belonged to a forgotten people called the Ancient Beringians, unknown to science until now.

Before now, there were only two recognised branches of early Native Americans (referred to as Northern and Southern). But when the researchers sequenced sunrise girl-child's genome – the earliest complete genetic profile of a New World human to date – to their surprise it matched neither.

Using genetic analysis and demographic modelling, the team concludes a single founding ancestral Native American group split from East Asians around 35,000 years ago, most likely somewhere in north-east Asia.

At some point, it's suspected these people moved as one in a single mass migration into North America, before – some 15,000 years or so later – the population split into two groups.

One of the groups became the Ancient Beringians – the other group were the ancestors of all other Native Americans – although it remains possible this division was already occurring before the Bering Land Bridge was crossed.

"We were able to show that people probably entered Alaska before 20,000 years ago," says evolutionary geneticist Eske Willerslev from the University of Cambridge in the UK.

"It's the first time that we have had direct genomic evidence that all Native Americans can be traced back to one source population, via a single, founding migration event."

Countless generations after the trek, sunrise girl-child and dawn twilight girl-child – thought to be first cousins – were born into an isolated people in the icy Alaskan wilderness of the Late Pleistocene.

Life would not have been easy, but the population as a whole – separated from those who journeyed elsewhere in the New World – lasted thousands of years before eventually being absorbed into other Native American populations.

Given the nature of this field of research – and the scope of the new findings – it's unlikely the new hypotheses will remain uncontested for long. But in the light of all the new evidence researchers are uncovering, it's clear the first settlers of America carried a more diverse lineage than we ever realised.

"[This is] the first direct evidence of the initial founding Native American population," Potter says. "It is markedly more complex than we thought."

The findings are reported in Nature.