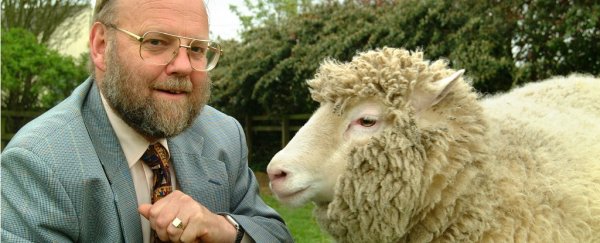

The chief scientist behind the creation of Dolly the Sheep – the world's first mammal cloned from an adult somatic cell – has called for the establishment of a biobank to preserve the biological tissue of endangered animals.

Speaking on the eve of the 20th anniversary of Dolly's birth on 5 July 1996, Sir Ian Wilmut said a modern-day Noah's Ark – functioning much like an animal-focused version of the 'Doomsday' Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway – could help save species from extinction.

"The absolute minimum we should do is preserve tissues from these animals in such a way they can be thawed and grown again," Wilmut, an embryologist from the University of Edinburgh in the UK, told the media.

Such a facility could preserve matter such as animal eggs and sperm, which could hypothetically help scientists to effectively resurrect species if they become extinct in the future.

But while researchers might one day be able to make viable embryos from stored cells and tissues, Wilmut acknowledges large gains would first need to be made in biological science – especially since a living surrogate female animal from another species would be needed to carry and give birth to any animal produced by the procedure.

If those issues can be addressed, Wilmut said the kinds of advances being made in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) – which scientists can use to generate all other kinds of cells in the body – could make an animal biobank a viable way to produce living animals.

"We are looking some distance into the future, but people are beginning to develop abilities to produce gametes (sperm and egg cells) from iPS cells," said Wilmut. "I would presume that one day, with the species which are really studied, we will be able to produce gametes, and therefore embryos."

Another means of resurrecting extinct animal species could lie in genetic editing processes, Wilmut said. Techniques such as CRISPR, which allow scientists to cut, copy, and paste individual fragments of an organism's DNA, might be able to make incremental changes to a living species over the course of several generations, until the species begins to genetically resemble an extinct species.

There's been a lot of controversy over the use of CRISPR in humans, since the genetic changes scientists introduce will persist in future generations, but Wilmut says he is against the idea of banning the procedure outright.

"I think as a principle there shouldn't be a simple red line that says 'no we don't'. The question is what's the benefit, what's the risk of mishap and does the one thing justify the other?" he said. "If there's a procedure that would enable you to either correct a disease or enhance somebody in some way, and approved within a broad context, then I would be in favour of it."

So far, scientists have had mixed results with resurrecting animal species, suggesting that we still have a way to go before we really know what we're doing.

Last year, researchers successfully implanted mammoth DNA into functioning elephant cells in petri dish as an experiment, but many previous attempts to bring back extinct animals have resulted in serious physical defects – with a Pyrenean ibex (aka bucardo) cloned in 2003 lasting only 7 minutes before dying of breathing difficulties.

While Wilmut advocates cloning science for the benefit of preserving endangered species, he's doubtful about the idea of people cloning their own pets. Last year, a couple in the UK paid a South Korean cloning company approximately US$100,000 to clone their boxer, Dylan, who died of a heart attack.

Wilmut says a pet's personality is a natural product of its upbringing, and in any case, the movement of cells during foetal development would likely ensure that no cloned animal would ever produce a perfect visual match to the original pet.

"[Y]ou can't clone a personality… In appearance and certainly personality it's likely to be very different," he said. "So people should consider whether they want to go away and buy another pet instead by natural means. It will probably be just as similar as a clone."