Physicists are used to quantum mechanics limiting how much we can know about the fundamental constituents of matter. But now, a couple of physicists have suggested that there are walls in the other direction too - someday, we'll have measured the biggest stuff in the Universe about as well as we can possibly measure it.

And even then, we won't know everything - and that's a problem.

Imagine a potato cannon that always shoots potatoes at exactly the same speed. Any high school physics student will tell you that whenever our imaginary cannon shoots potatoes at the same angle, the potatoes are going to go the same distance before hitting the ground - as long as the cannon's on Earth.

In other words, it only takes one number - the angle of the cannon - to produce exactly the same shot.

Modern cosmology tells us that the Universe, as far as things like the distribution of galaxies are concerned, isn't too different from our potato cannon: if you specify enough numbers, the end product will be exactly the same.

So how many numbers does it take to reproduce our Universe? Well, you need two for the densities of visible matter and dark matter that existed when the Universe began. Then there are three numbers telling you how the first visible and dark matter were distributed. They bring us up to a total of five.

You also need to know something about the temperature of the Big Bang. That makes six. Remarkably, that's the whole list: six numbers get you a Universe, just like one number got you a potato shot.

Those six numbers alone determine how galaxies form and arrange themselves; they made the fingerprint of the Big Bang - called the cosmic microwave background (CMB) - look like it does. These numbers also explain the last 13 billion years of cosmic evolution.

As far cosmologists can tell, if you restart the Universe with those six numbers exactly the same, and with the same laws of physics, you'll end up with the exact same Universe we have today, at least as far as big structures are concerned. The details might differ, but the scaffolding would be identical.

If that's true, our understanding of the entire Universe comes down to measuring those numbers more and more accurately.

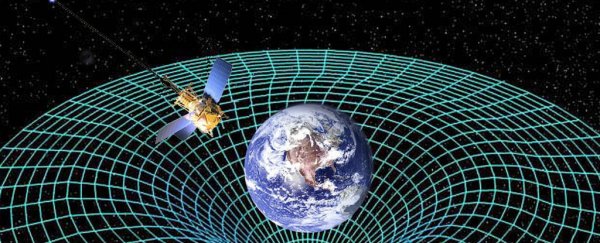

Scientists measure these numbers using things like the cosmic microwave background. The CMB tells them the temperature of the Universe in every conceivable direction, and scientists have measured these temperatures down to hundredths of thousandths of degrees.

Such precision puts really tight constraints on the six numbers: if something like the density of matter in the early Universe were different than we think, it would have made temperature patterns in the CMB that scientists haven't seen.

Future measurements will be even more accurate than the ones we have now, locking the numbers in even more.

But our measurements of the CMB can't improve forever, which is where physicists Yin-Zhe Ma from the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa and Douglas Scott from the University of British Columbia, Canada come in.

For one thing, astronomical experiments will always have uncertainties, because of things like galaxies being in the way, and dust messing up the satellites. But even if it were possible to measure infinitely precisely, the CMB only has so much to offer us.

The sky to your left is a certain temperature, the sky to your right is another temperature, and, unless modern cosmology is missing something major about the way the Universe works, there can only be so much difference between those two.

That maximum possible difference between the temperatures puts a limit on how much information we could ever get out of the CMB. And a limit on how much we can learn from the CMB limits our ability to know those six numbers.

This isn't just for the CMB, either. Ma and Scott point out that all of the large-scale things we measure about the Universe have the same behaviour: there's always some fundamental limit to how spread out the values of that thing can be, and that limit restricts how well we can nail down the numbers that describe the Universe as a whole.

But don't let this stop you from becoming a cosmologist. We can't know how long we have before cosmology hits walls for all of the different ways of measuring the Universe, but it'll probably be a very long time.

There's still a lot left to learn. Like the authors write, "future cosmologists will always be able to do better if they are inventive enough".

Their study has been published in the journalPhysical Review D.