The intricate and distinctive brushstrokes a painter makes aren't just a window into the artist's soul – they could also offer a unique and early perspective on neurodegenerative disorders, according to a new study.

Researchers in the UK analysed the painting styles in more than 2,000 artworks by seven famous painters – including Salvador Dali, Pablo Picasso, and Claude Monet – and found that fractal patterns in the brushstrokes were indicative of cognitive changes brought on by conditions like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease.

Fractals are self-repeating geometrical patterns that replicate at every scale of size, and are often found in nature, such as in the structure of snowflakes and plants, or in the ways that rivers branch.

To be clear, the method behind this research is a little controversial. In the world of art, fractal analysis techniques have sought to demonstrate that these self-repeating patterns can be found in paintings, with methods such as box counting showing that the same shapes appear to replicate as you zoom in closer on artworks.

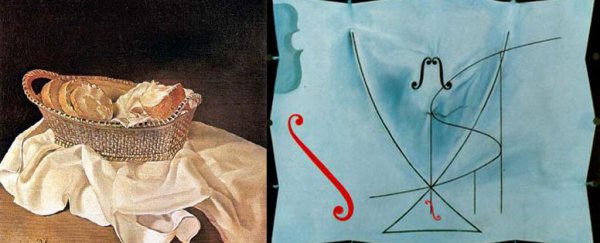

Salvador Dali's The Basket of Bread (1926) and The Swallow's Tail (1983). Credit: Wikimedia

Salvador Dali's The Basket of Bread (1926) and The Swallow's Tail (1983). Credit: Wikimedia

This kind of analysis was previously used to suggest that artworks by abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock contained fractal patterns that could determine his authorship of the paintings.

But subsequent research later disputed the findings, suggesting that simply by using Photoshop, anybody could easily and effectively emulate the debatable 'fractal' characteristics in Pollock's work.

Undeterred by that rebuttal, researchers from the University of Liverpool in the UK have now used fractal analysis to examine 2,092 paintings spanning the careers of seven other famous artists, and they say the extent of fractal complexity – called fractal dimension – in the artworks changed as the artists aged or succumbed to neurodegenerative conditions. But it wasn't a clear-cut increase or decrease.

In the study, the researchers looked at artworks by Salvador Dali and Norval Morrisseau (who had Parkinson's disease), James Brooks and Willem de Kooning (who had Alzheimer's), and also three other famous painters – Marc Chagall, Pablo Picasso, and Claude Monet – who didn't have recorded neurodegenerative disorders, but were used for comparative purposes.

In all cases, the fractal dimension changed. For Chagall, Picasso, and Monet – the measure generally increased as they aged.

But in a sharp contrast, the artworks of de Kooning and Brooks – who both had Alzheimer's – saw the fractal dimension fall steeply between the ages of 40 and 80.

Willem de Kooning's Woman III (1953) and Untitled (1976). Credit: Wikimedia & Pedro Ribeiro Simões/Flickr

Willem de Kooning's Woman III (1953) and Untitled (1976). Credit: Wikimedia & Pedro Ribeiro Simões/Flickr

For the artists with Parkinson's – Dali and Morrisseau – the measure rose and fell like an inverted U shape, rising in their 20s, peaking when they were about 50 to 60 years of age, and then declining after.

The researchers' acknowledge that their findings aren't a conclusive way of diagnosing these conditions, but say the results show another way of seeing how neurodegenerative disorders affect the brain.

"I don't believe this will be a tool for diagnosis, but I do think it will trigger people to consider new directions for research into dementia," psychologist Alex Forsythe told Ian Sample at The Guardian.

"The [fractal] information seems to be like a footprint that artists leave in their art. They paint within a normal range, but when something is happening the brain, it starts to change quite radically."

But not everybody is convinced by the findings.

Physicist Kate Brown from Hamilton College in New York – who was involved with the 2006 study that disputed the existence of fractals in Pollock's artworks – called the new paper "complete and utter nonsense".

Brown argues that the extent to which patterns repeat in artworks is too shallow and vague to be considered true fractal replication.

"The whole premise of 'fractal expressionism' is completely false," she told The Guardian.

"Since our work came out, claims of fractals in Pollock's work have largely disappeared from peer-reviewed physics journals. But it seems that the fractal zealots have managed to exert some influence in psychology."

By contrast, the researcher who originally used fractal analysis to examine Pollock's work – Richard Taylor from the University of Oregon – is considerably more upbeat, describing the new research as a "magnificent demonstration of art and science coming together".

"This work could hopefully be used to learn more about conditions such as dementia," he said. "To me, the most inspiring message to come out of this work is that beautiful artworks can result from pathological conditions."

It's likely the debate over the merits of fractal analysis in artworks will be reignited in light of the publication of the new research.

But leaving aside the controversy for a moment, any research that can highlight potential new ways that we can examine these crippling neurodegenerative conditions is worthy of paying attention to – and hopefully this new analysis can inspire additional findings that will unite and not simply divide scientists.

"Art has long been embraced by psychologists [as] an effective method of improving the quality of life for those persons living with cognitive disorders," Forsythe said in a statement.

"We hope that our innovation may open up new research directions that will help to diagnose neurological disease in the early stages."

The findings are reported in Neuropsychology.