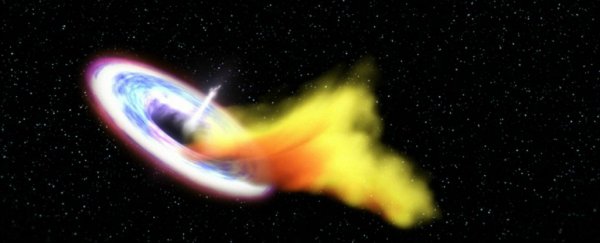

For the first time, researchers have spotted a star being swallowed up by a black hole, and then watched as some of the star's matter was ejected back out as a flare of plasma moving at nearly the speed of light - a process that's been compared to a cosmic 'burp'.

Scientists have seen black holes swallowing stars before and they've also separately detected these mysterious jets of matter blasting out, but until now no one had been fast enough with their telescopes to link the two events, and were never able to witness them occurring in sequence.

"These events are extremely rare," said lead researcher Sjoert van Velzen from Johns Hopkins University. "It's the first time we see everything from the stellar destruction followed by the launch of a conical outflow, also called a jet, and we watched it unfold over several months."

So why is the observation so exciting? It confirms what astrophysicists had predicted could happen when a black hole is force-fed a large amount of gas (in this case, a whole star) - a fast-moving jet of plasma can escape from near the event horizon.

Until recently, it was assumed that black holes had such strong gravity that nothing, not even light, could escape them. But researchers such as Stephen Hawking and Gerard 't Hooft have been able to show that energy can escape a black hole, and now it seems that matter can escape from near the event horizon too.

The unlucky star that was gobbled up was around the size of our Sun, and the black hole in question was a relatively light one, located at the centre of a galaxy around 300 million light-years away.

The first observation of the star being destroyed was made on Twitter in early December 2014 by a team at Ohio State University that had spotted the event using an optical telescope in Hawaii.

Immediately, van Velzen and a group of international researchers jumped on the event, and pointed a bunch of radio telescopes in the direction of the galaxy as fast as possible, in the hopes of catching the erupting plasma jet they predicted would soon follow.

They were just in time to catch the action, and the team was able to witness the event from a range of satellites and telescopes, creating a picture of the event in X-ray, radio, and optical signals. Their research has been published in Science.

The researchers ruled out the possibility that the light being beamed out was from something called an 'accretion disk', which forms when a black hole is sucking up matter from space, and that then supported the hypothesis that the jet was indeed from a sucked up star.

"The destruction of a star by a black hole is beautifully complicated, and far from understood," said van Velzen. "From our observations, we learn the streams of stellar debris can organise and make a jet rather quickly, which is valuable input for constructing a complete theory of these events."

There's still a lot we have to learn about how black holes work, but we're making progress, and that's pretty cool.