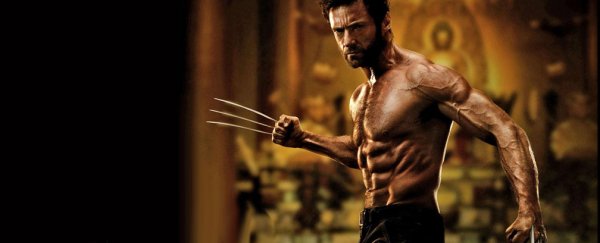

Insensitivity to pain and virtually unbreakable bones are the hallmarks of superheroes like the X-Men's Wolverine, but they're also real-life genetic conditions that affect a very rare minority of people.

And now the hunt is on to unlock the mystery of how these genetic irregularities come to exist in everyday superheroes. The science is potentially worth billions to pharmaceutical companies that want to use these discoveries to contrive all kinds of new wonder drugs to make our lives better.

According to a report by Caroline Chen for Bloomberg, the DNA of genetic outliers such as Steven Pete and Timothy Dreyer could be worth billions to medical researchers. Pete, 34, lives in Kelso, Washington, and is gifted with a congenital insensitivity to pain, due to a rare combination of two otherwise benign mutations passed down by his mother and father. Dreyer, 25, lives in Johannesburg, South Africa, and displays an extremely rare bone condition called sclerosteosis, which makes his bones so dense they are extremely hard to break.

While the conditions may sound like awesome superhero powers (and they kind of are), they're just as much a curse as a blessing for these men, delivering terrible side effects in addition to the obvious advantages. Pete's insensitivity to pain caused him to chew off his own tongue as a baby, and his left leg suffers permanent damage from injuries in his youth he never felt occurring. Dreyer's bone condition might help him survive a collision with a car like the Colossus or The Thing, but it's also caused cranial pressure that's led to hearing loss.

Sad as it is that these outliers suffer such afflictions brought on by their genetic makeup, their unique DNA is a source of great inspiration for the pharmaceutical industry, which hopes to discover a new generation of drugs made possible by their conditions.

According to Chen, new cholesterol-lowering medications will soon hit the market in the US, derived from a gene mutation evidenced in one case by an aerobics instructor with a remarkably low cholesterol count.

Research into sclerosteosis is being used to combat osteoporosis by encouraging bone regrowth, while a greater scientific understanding of what causes Pete's insensitivity to pain could be hugely important to the pain relief industry, which Chen says is worth US$18 billion annually.

"The beauty of the [pain insensitivity] phenotype is that you're largely normal," Morgan Sheng, a vice president at Genentech, told her, referring to how people with congenital pain insensitivity don't appear to display any obvious physical markers of their condition. "You want to just prevent pain and not cause a bunch of other problems."

The promise of such wonder drugs may not do much to improve the quality of life for people like Pete and Dreyer, but at least they'll know their genetic contributions to scientific research could offer huge benefits one day to the rest of us: everyday powerless folk, or "puny humans", as the Hulk might say.