A study on the vaginal bacteria of South African women has revealed that a certain type of bacteria is able to break down a common drug used for the prevention of HIV.

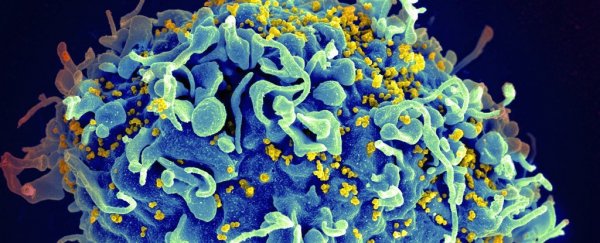

Annually, more than 1 million women are infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). HIV infection rates among women are a major health concern, as HIV can be passed from mothers to their children during pregnancy, childbirth ,and breastfeeding.

"I believe this will change the way we approach HIV prevention studies in women," lead researcher Nichole Klatt, from the University of Washington, told ScienceAlert.

The microbicide drug, tenofovir, is widely used to combat the spread of HIV, and works by inhibiting the process that allows HIV to replicate. While tenofovir routinely protects men against HIV infection, women using the same drug might not see the same results.

But what exactly does the vagina have to do with drug administration?

In Africa, tenofovir is being applied in a gel directly into the vagina. Taking a tablet isn't always ideal in Sub-Saharan Africa, and the focus of prevention here is to stop the spread of HIV at the site of infection during sex.

Other studies have revealed that the vagina may contain bacteria that acts as a sort of 'biological condom', protecting against the infection of HIV and STIs.

To investigate the potentially negative effects these bacteria are having on tenofovir, Klatt and her team collected vaginal swabs from 688 South African women as they participated in a clinical trial into the efficiency of an intravaginal gel against HIV infection.

The team found that there were two major types of vaginal bacteria present in the sample group - one contained Lactobacillus, and the other contained Gardnerella vaginalis.

Of the two major types of vaginal bacteria, the women with non-lactobacillus bacteria had a reduction of HIV infection of only 18 percent, while those with Lactobacillus had a reduction in HIV infection rate of 61 percent when using the gel - a threefold increase in protection.

The scientists investigated further, and discovered that G. vaginalis could metabolise and breakdown the active form of the drug, rendering it useless in the fight against the spread of HIV.

"These data demonstrate that vaginal microbiota must be accounted for and to improve efficacy of HIV prevention, novel interventions to enhance Lactobacillus and decrease Gardnerella and other BV-associated bacteria are needed," Klatt told ScienceAlert.

The scientists hope that the results will inform the ways in which the drug is administered based on the bacteria present in a patient's vagina.

"We are now excited to be forging the way ahead in pharmacomicrobiomics studies in HIV and other diseases. Specifically, we are assessing other drugs that bacteria may interact with in the vagina, and the specific mechanisms underlying this," says Klatt.

"We are also developing systems to assess drug-microbiota interactions in other diseases such as IBD and cancer, where mechanisms underlying variable drug efficacy are unknown."

The research is published in Science.