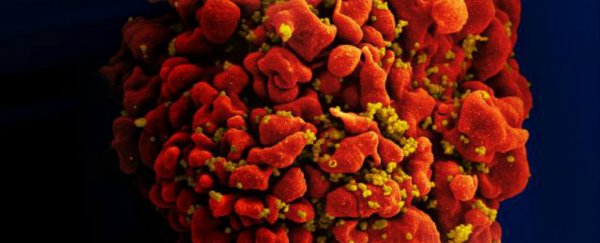

We all got really excited a few weeks ago when researchers announced they'd removed HIV from human immune cells using new gene-editing technology called CRISPR/Cas-9, or ' CRISPR' for short, which works like a pair of molecular scissors to cut and paste DNA.

As far as we know, that specific result is holding up just fine, but a separate study has now revealed that, worryingly, HIV can evolve to survive CRISPR attacks in just two weeks. Even worse, the attack itself could actually be introducing mutations that make the virus stronger. So… damn.

To give you a quick back story, when HIV infects our immune cells, it inserts its genome into our cells' DNA, and then hijacks the cell to churn out more copies of itself, like the total jerk it is.

While antiretroviral drugs can successfully keep active HIV infections under control and extend patients' lifespans, no one has been able to get dormant HIV DNA out of our cells, so it's always lying in wait for the day the drugs stop.

But since the development of CRISPR system back in 2012, scientists have had some pretty good results when it comes to attacking the dormant HIV genome.

Last year, for example, a team led by Chen Liang from McGill University in Canada was able to use CRISPR to to cut up the viral DNA that was hiding in human immune cells, and it appeared to effectively disable HIV.

But two weeks later, the cells were pumping out copies of the virus again - and this time the virus had mutated to be stronger and resistant to CRISPR. The researchers have published the new, slightly depressing, results in Cell Reports (site is currently down).

Lian and his team had thought that by cutting HIV up into little pieces using CRISPR, the cell would try to patch it up (as it automatically does) and introduce 'scar tissue' into the sequence that would stop the virus from replicating and effectively disable it.

And while that initially appeared to be happening, some of the viruses survived, and the scar tissue alterations had actually made them stronger - even worse, because their genetic sequences had changed thanks to these new mutations, CRISPR was no longer able to attach to it to attack it again.

"On the one hand, CRISPR inhibits HIV, but on the other, it helps the virus to escape and survive," Liang told New Scientist.

To be fair, it's not hugely surprising that HIV has managed to evolve past yet another of our attempts to stop it - we've long known that it could mutate to survive most antiviral drugs we've thrown at it. But what is surprising in this instance is just how fast HIV bounced back… and the fact that our own cells seemed to have given the virus these handy mutations.

"The surprise is that the resistance mutations are not the products of error-prone viral DNA copying, but rather are created by the cell's own repair machinery," Liang added.

It's not all bad news though. Liang now thinks that a better approach might be cutting the HIV virus at multiple sites in the DNA, rather than just the one they targeted in their initial experiment. He also thinks experimenting with pairing CRISPR with enzymes other than Cas-9 could work.

And as we mentioned at the start of this piece, the research from a few weeks ago, which successfully saw the HIV virus edited out of human immune cells altogether, still seems to be working - and is in itself a huge, exciting step towards a cure.

"I assume if we target multiple sites in the HIV DNA, there's a good chance of achieving a long suppression of the virus," Liang told Mic. "Fortunately, the field is advancing very fast … I think CRISPR is easy and specific enough to use. I think we'll see better tools [to fight HIV] soon."

Fingers crossed that now we know the flaws of the CRISPR/Cas-9 system, we'll get better at using it to stop HIV for good. Because despite this latest study, it still seems to be our best chance of overcoming the virus.