Chemotherapy is one of the key weapons in our fight against cancer, but it comes with a whole host of unwanted side effects and damage to the surrounding, healthy areas of the body. So an international team of researchers has come up with what they think could be a much less toxic way of delivering the treatment, and it's based around 'cluster bombs' of nanoparticles.

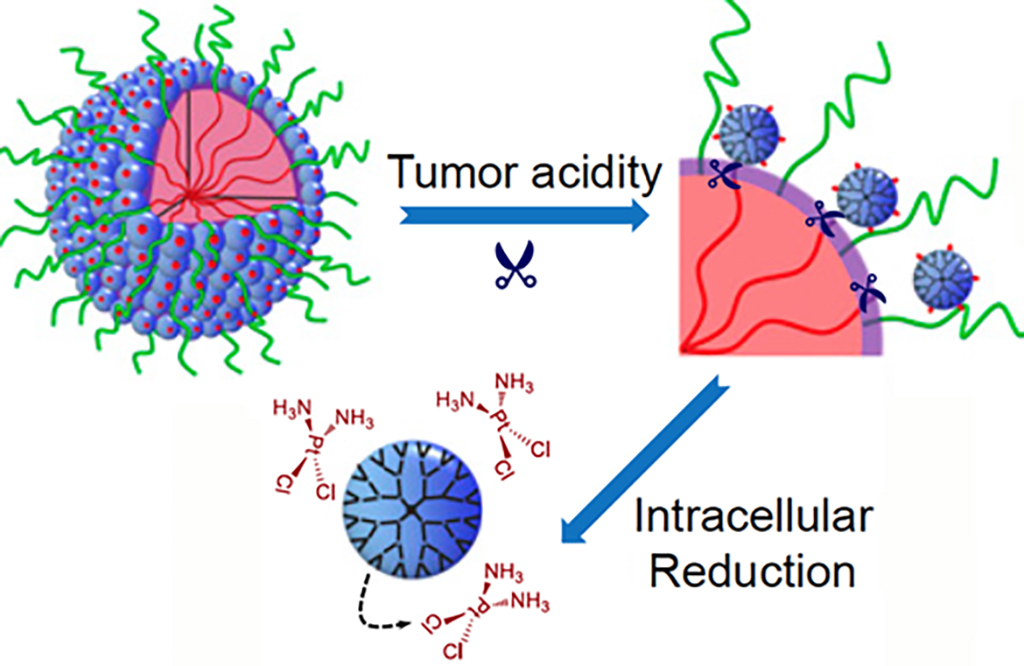

The new procedure is designed to improve the delivery of the chemotherapy drug cisplatin. It works using tiny nanoparticles, just 100 nanometres wide, which are loaded with drugs and transported to the tumour site through blood vessels. Once they reach their destination, the acidic environment around the cancer cells causes them to break up into 5-nanometre-wide particles, which can then move inside the tumour cells.

At this point, the cisplatin can do its work from inside the tumour cells, damaging the cancerous DNA to effectively kill them off. To give you some idea of the scale, you can fit a million nanometres inside a millimetre.

In tests on lab mice, the teams from Emory University in the US and the University of Science and Technology of China found that the concentration of cisplatin that reached the tumours was seven times higher than normal. And if more of the drug is reaching its intended target, that means less of it is leaking out into the rest of the body, so unwanted side effects are reduced.

The team reports that when cisplatin is delivered in the usual way, it achieved a 10 percent growth inhibition in tests on lung cancer. That figure shot up to 95 percent using the new nanoparticle method.

Survival rates were also improved when the process was used on mice with breast cancer tumours. "In the metastatic breast cancer model, treating mice with cisplatin clothed in nanoparticles prolonged animal survival by weeks," the Emory team reports. "50 percent of the mice were surviving at 54 days with nanoparticles, compared with 37 days for the same dose of free cisplatin."

Emory University

Emory University

Of course, while the results are looking promising, the technique has so far only been tested on mice. Adjusting the technique to be used safely in humans is going to take some time, and there are still some serious questions about how to ensure that patients can safely rid themselves of the nanoparticles once they've done their job.

But one thing's for sure, we really do need to find a better alternative to chemotherapy as it's currently delivered, and this could be a step in the right direction.

"The negative side effects of cisplatin are a long-standing limitation for conventional chemotherapy," said one of the researchers, Jinzhi Du, from Emory University. "In our study, the delivery system was able to improve tumour penetration to reach more cancer cells, as well as release the drugs specifically inside cancer cells through their size-transition property."

It's not just the small size of the original nanoparticles that makes the treatment so effective, it's also the way they automatically break up into smaller 'bomblets' once they reach the site of the tumour. Eventually, the researchers suggest, the treatment could be applied to various different types of cancer.

The study has been published in the journal PNAS.