Will we one day be able to disable the ageing process? It sounds like an impossible goal, but scientists from Northwestern University in the US have found a way to turn off the 'genetic switch' that causes us to get older - in worms at least. While it won't give us the keys to immortality just yet, the discovery could lead to new ways of making us more productive and active in the latter years of our lives.

According to the study, this genetic switch is automatically flipped when a worm reaches reproductive maturity. Stress responses that originally protect its cells by keeping vital proteins folded and functional are switched off at this point, and the ageing process begins in earnest - with the switch disabled, the cells kept up their earlier level of resistance, making the worm better able to handle the wear and tear of growing older.

It's a big jump from worms to human beings of course, but the two researchers behind these experiments say there are enough common biological links to suggest that the same technique could be applied to other animals. The key moment is associated with reproduction, because it's at this point that the future of the species has been guaranteed - once the next generation is born, the current generation can get out of the way.

"[The study] has told us that ageing is not a continuum of various events, which a lot of people thought it was," Richard Morimoto, the senior author of the study, said in a press release. "In a system where we can actually do the experiments, we discover a switch that is very precise for ageing… Our findings suggest there should be a way to turn this genetic switch back on and protect our ageing cells by increasing their ability to resist stress."

"Wouldn't it be better for society if people could be healthy and productive for a longer period during their lifetime?" adds Morimoto. "I am very interested in keeping the quality control systems optimal as long as we can, and now we have a target."

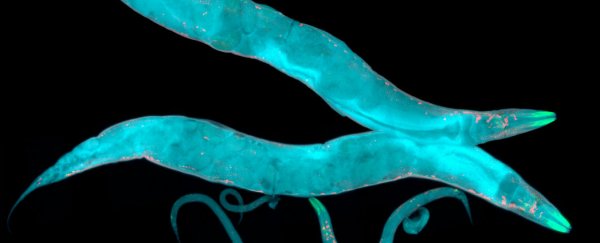

Johnathan Labbadia, a postdoctoral fellow in Morimoto's lab, also assisted in the experiments, which build on a decade of previous research. The scientists focused on the germline and soma tissues, blocking biochemical signals from the former to delay the decline in the condition of the latter. These changes weren't immediately obvious in the worms used as test subjects, but they're identifiable at a molecular level.

"This was fascinating to see," concludes Morimoto. "We had, in a sense, a super stress-resistant animal that is robust against all kinds of cellular stress and protein damage."

A long way down the line, we might be able to reproduce the same kind of resistance for our own cells. The report has just been published in the journal Molecular Cell.