Over the past year, there's been a whole lot of excitement about the electromagnetic propulsion drive, or EM Drive - a scientifically impossible engine that's defied pretty much everyone's expectations by continuing to stand up to experimental scrutiny.

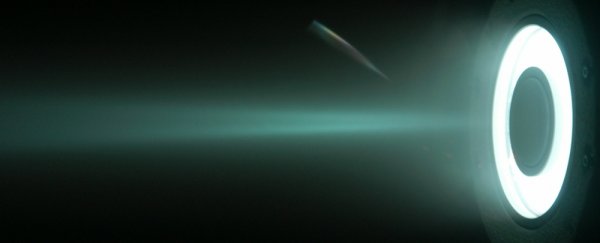

The drive is so exciting because it produces huge amounts of propulsion that could theoretically blast us to Mars in just 70 days, without the need for heavy and expensive rocket fuel. Instead, it's apparently propelled forward by microwaves bouncing back and forth inside an enclosed chamber, and this is what makes the drive so powerful, and at the same time so controversial.

As efficient as this type of propulsion may sound, it defies one of the fundamental concepts of physics - the conservation of momentum, which states that for something to be propelled forward, some kind of propellant needs to be pushed out in the opposite direction.

For that reason, the drive was widely laughed at and ignored when it was invented by English researcher Roger Shawyer in the early 2000s. But a few years later, a team of Chinese scientists decided to build their own version, and to everyone's surprise, it actually worked. Then an American inventor did the same, and convinced NASA's Eagleworks Laboratories, headed up by Harold 'Sonny' White, to test it.

The real excitement began when those Eagleworks researchers admitted back in March that, despite more than a year of trying to poke holes in the EM Drive, it just kept on working - even inside a vacuum. This debunked some of their most common theories about what might be causing the anomaly.

Now Martin Tajmar, a professor and chair for Space Systems at Dresden University of Technology in Germany, has played around with his own EM Drive, and has once again shown that it produces thrust - albeit for reasons he can't explain.

Tajmar presented his results at the 2015 American Institute for Aeronautics and Astronautics' Propulsion and Energy Forum and Exposition in Florida on 27 July, and you can read his paper here. He has a long history of experimentally testing (and debunking) breakthrough propulsion systems, so his results are a pretty big deal for those looking for outside verification of the EM Drive.

To top it off, his system produced a similar amount of thrust as was originally predicted by Shawyer, which is several thousand times greater than a standard photon rocket.

"Our test campaign cannot confirm or refute the claims of the EM Drive but intends to independently assess possible side-effects in the measurements [sic] methods used so far," Tajmar and graduate student Georg Fiedler write in their conference abstract. "Nevertheless, we do observe thrust close to the actual predictions after eliminating many possible error sources that should warrant further investigation into the phenomena."

So where does all of this leave us with the EM Drive? While it's fun to speculate about just how revolutionary it could be for humanity, what we really need now are results published in a peer-reviewed journal - which is something that Shawyer claims he is just a few months away from doing, as David Hambling reports for Wired.

But even then, until we can figure out exactly how the EM Drive works, it's unlikely that the idea is going to be taken seriously by the scientific community. For now, all scientists can do is keep testing the system in a range of different environments and try to work out what's causing this "impossible" thrust.

It might turn out that we need to rewrite some of our laws of physics in order to explain how the drive works. But if that opens up the possibility of human travel throughout the Solar System - and, more importantly, beyond - then it's a sacrifice we're definitely willing to make. Bring on the next set of tests.

Update 29 June 2015: As predicted, a lot of experts in the field have responded to Tajmar's independent confirmation with skepticism over the past 24 hours. Their concerns centre on the problems flagged in our original story - the fact that no one can explain exactly how the EM Drive works, and that there's still no peer-reviewed research showing that the thrust production isn't an artefact of some other experimental variable. But Eric W. Davis, a physicist at the Institute for Advanced Studies at Austin, pointed out to io9's George Dvorsky that there also appear to be flaws in Tajmar's experiment.

"I noted in [the study's] conclusion paragraphs that [Tajmar's] apparatus was producing hundreds of micro-Newtons of thrust when it got very hot and that his measuring instrumentation is not very accurate when the apparatus becomes hot," Davis told io9. "He also stated that he was still recording thrust signals even after the electrical power was turned off which is a huge key clue that his thrust measurements are all systematic artifact false positive thrust signals."

"The experiment is quite detailed but no theoretical account for momentum violation is given by him, which will cause peer reviews and technical journal editors to reject his paper should it be submitted to any of the peer-review physics and aerospace journals," he added.