For the first time, researchers have successfully grown human cells inside early-stage pig embryos in the lab, creating pig-human hybrids, which the researchers describe as interspecies chimeras.

While still early days, the experiment might one day lead to lab-grown human organs that can be transplanted into those who need them, potentially saving thousands of lives.

In the experiment, researchers in the US injected human stem cells into early-stage pig embryos. These hybrid embryos were then transferred into surrogate sows and allowed to develop until the first trimester.

More than 150 of the embryos developed into chimeras, which meant that they had developed the precursors of organs including the heart and liver, but they contained a small amount of human cells - around one in 10,000 of the hybrids' cells were human.

This is a proof-of-concept experiment showing that human-pig hybrids are possible. The ultimate goal is to find a way to use these lab-grown human parts for transplants.

"Our findings may offer hope for advancing science and medicine by providing an unprecedented ability to study early embryo development and organ formation, as well as a potential new avenue for medical therapies," said team member Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, from the Salk Institute in California.

"We have shown that a precisely targeted technology can allow an organism from one species to produce a specific organ composed of cells from another species."

Izpisua Belmonte and his team previously performed experiments to create interspecies chimeras in the lab back in 2015.

Their early study successfully integrated human stem cells into mouse embryos, which showed that human stem cells could develop inside another species, creating a world-first chimera.

The term chimera comes from a legend in Greek mythology, describing a monster which was often depicted as a lion with a goat's head sticking from the side of its neck, and a snake for a tail. In biology, it describes the natural or artificial development of one individual organism containing cells from another, and scientists have long been fascinated by them.

"This provides us with an important tool for studying species evolution, biology and disease, and may lead ultimately to the ability to grow human organs for transplant," Izpisua Belmonte explains.

Building upon their previous research, the team has now announced that they have successfully pulled off a series of new experiments that push the field even further.

The human-pig embryo was the culmination of these experiments, but there were two other important steps along the way. The team's first experiment involved using CRISPR-Cas9, a versatile new tool in gene-editing technology, to turn off the genes that produce a pancreas in mice. They then inserted rat stem cells into the mouse that contained the genetic information needed to grow a rat pancreas.

These embryos, despite having a different species' pancreas growing inside of them, developed normally, which prompted them to try similar experiments, such as growing a set of rat eyes and a rat heart inside a mouse.

Most notably, they were also able to grow a gallbladder inside the mouse from rat stem cells, which is unique because rats don't even have gallbladders.

"Our rodent experiments reveal a profound secret, that a developing mouse was able to unlock a gallbladder developmental program in rat cells that is normally suppressed during rat development," explains team member Jun Wu, also from the Salk Institute.

"This highlights the importance of the host environment in controlling organ development and evolutionary speciation."

A second experiment tried adding rat and mouse stem cells to an early stage pig embryo. Interestingly, after implanting these cell bundles back into pigs for continued gestation of about four weeks, there was no sign of the rodent stem cells.

A third experiment kicked it up a notch - they added human stem cells to clusters of embryonic pig cells, and to embryonic cow cells, forming two new chimeras. After a couple of days they investigated the cells and found the human cells were still growing.

These experiments all led up to the biggest of the team's findings: the ability to create a human-pig hybrid that would continue to develop inside a pig's uterus.

To do so, the team took human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells and inserted them into a pig embryo as before. They then implanted the embryos into sows and allowed the cells to gestate for four weeks. After that time, they decided to see how everything was going.

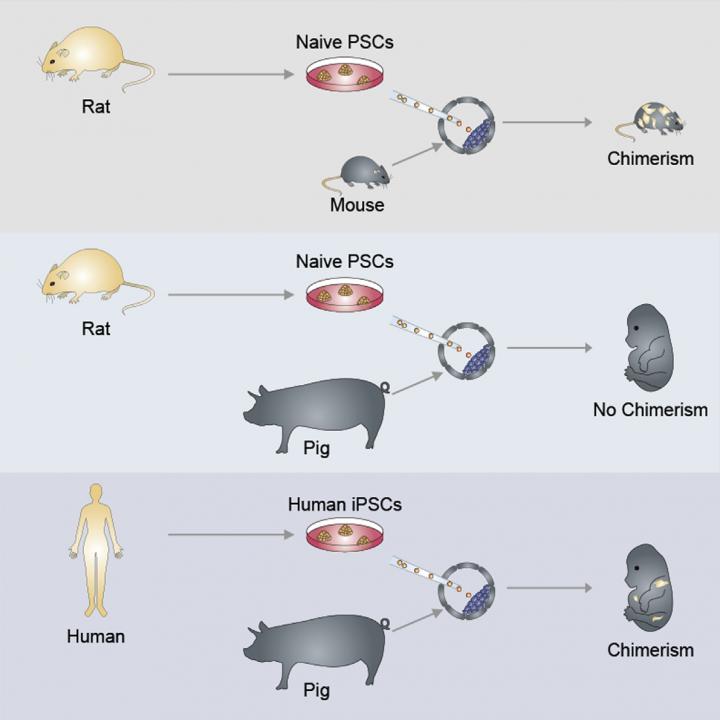

Here's a handy graphic that explains the different processes in more detail:

Wu et al

Wu et al

They found that some of the human cells inside the embryos were starting to specialise and become precursors to human tissue, indicating the cells were living and reproducing inside the pig embryo.

This is important because pigs grow large enough to develop organs that would be an appropriate size for a human.

Though the human stem cells didn't work inside the implanted pig embryos as well as the rat's did inside the mice, this is the first time a human-pig chimera has been successfully created in the lab, a large step toward the team's true end goal of figuring out how to grow organs in the lab.

"Of course, the ultimate goal of chimeric research is to learn whether we can use stem-cell and gene-editing technologies to generate genetically-matched human tissues and organs, and we are very optimistic that continued work will lead to eventual success," Izpisua Belmonte said.

"But in the process we are gaining a better understanding of species evolution as well as human embryogenesis and disease that is difficult to get in other ways."

As you can probably guess, this type of research brings up a bunch of safety and ethical concerns.

A significant objection is the opportunity for viruses to more easily jump a species barrier which was previously closed to them. There is also the 'ick' factor of such an intimate mixing of human and animal tissues for medical reasons, as well as the concern that these hybrid pigs could develop more human brains.

"The idea of having an animal being born composing of human cells creates some feelings that need to be addressed," Izpisua Belmonte told Hannah Devlin at The Guardian.

The hybrid embryos in this experiment were terminated after 28 days of development (the first trimester for pigs) to avoid further ethical concerns.

No one really has any answers for these hypothetical questions, which is partly what makes the research seem so scary. In fact, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has previously issued a moratorium on human chimera research, which they say they are in the process of lifting.

But it's also important to consider that 22 people die every day in the United States waiting for an organ transplant, and a person is added to the waiting list every 10 minutes. Which is why many people feel it's important that this research continues, as long as it's well regulated.

The team's work was published in Cell. Check out the video below to hear the team discuss their results.