Upcoming missions to Mars have grabbed plenty of headlines in recent years, but before we set off for the Red Planet, a lot more research is needed – and that's why NASA has a new plan for sending astronauts into orbit around the Moon.

It's been a while – we last set foot on the Moon in 1972. But NASA thinks the cislunar orbit (between the Moon and the Earth) is going to be an essential testing site and launching pad for reaching Mars in the 2030s.

As NASA's Greg Williams explained this week at the Humans to Mars Summit in Washington DC, the Moon mission is on the slate for 2027 and could see a crew spending a year sailing above the lunar surface.

That extended stay in space would be preceded by at least five missions, some manned and some unmanned, to lug bits of equipment towards the Moon. That kit would include a habitat for crew members as well as the Deep Space Transport spacecraft that NASA has in the works to take people all the way to Mars.

"If we could conduct a year-long crewed mission on this Deep Space Transport in cislunar space, we believe we will know enough that we could then send this thing, crewed, on a 1,000-day mission to the Mars system and back," Williams said, as reported by Calla Cofield at Space.com.

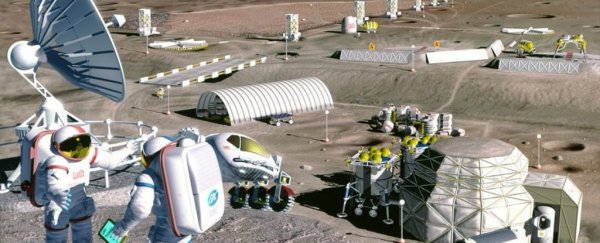

NASA's long-term plans for reaching Mars. Credit: NASA

NASA's long-term plans for reaching Mars. Credit: NASA

Right now the year-long cislunar mission doesn't have an official name. It was originally referred to as a "shakedown cruise", a term used by the Navy to describe a trip that tests the performance of a new ship.

If you've seen any gangster films though, you'll know that shakedown has other meanings too, so that name has been shelved.

As NASA has previously announced, the aim is to build a Deep Space Gateway that orbits the Moon and that can be used as a launching post for missions into deeper space, including journeys to Mars.

Using its most powerful rocket yet, the Space Launch System (SLS), the agency wants to start shifting hardware into space as early as next year, including a power and propulsion bus and an airlock for visiting vehicles to dock at.

All of these details are still "evolving", according to Williams, and we don't have any further information on how astronauts will be spending their 365 days circling the Moon. Everything they learn, though, will help with a mission to Mars.

Meanwhile scientists are still busy studying the effects of long-term trips to space on the human body. Recent research found that even a short trip outside of Earth's atmosphere could lead to liver disease in mice.

On top of that, after Scott Kelly's 340 days up in space, NASA found evidence of strains on vision, bone density, muscles and sleep patterns, so there's still a lot of work to do before we can make sure someone taking a 1,000-day round trip to Mars is going to be safe.

Between now and our trip to Mars, NASA is looking to partner up with firms such as SpaceX and Blue Origin to explore the possibilities for our jaunt to the Red Planet.

"We're trying to lead this journey to Mars with a broad range of partnerships," Williams added. "One of the things we'll be doing over the next few years is putting that package together."

The ultimate aim is working out "how we can together, with NASA in an orchestrating role, really move out on these crewed missions to Mars" says Williams.