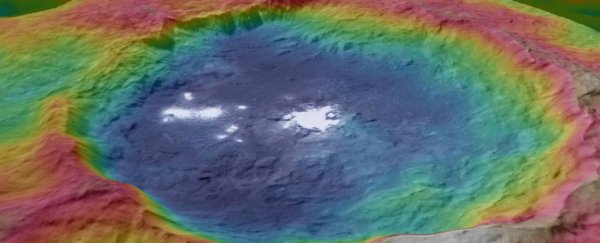

For months, NASA scientists (and the rest of us playing along at home) have been puzzling over a series of mysterious bright patches spotted in the middle of a huge crater on the dwarf planet Ceres.

First seen by the Dawn spacecraft, which is now steadily orbiting closer and closer to Ceres, NASA's original assumption was that the patches were made of ice, but the wavelengths of light being reflected suggested otherwise. And despite coming up with a whole lot of hypotheses since then, they've publicly remained stumped as to what could be causing the patches - until now.

At the European Planetary Science Congress in France at the end of last month, Dawn's principal investigator Chris Russell told scientists that they now believe the patches, which are located in the Occator crater, are huge salt deposits. "We know it's not ice and we're pretty sure it's salt, but we don't know exactly what salt at the present time," said Russell in his address, which has since been posted online.

Ice was the most obvious guess for the highly reflective patches, because Ceres is believed to harbour a huge ocean beneath its surface. In fact, the dwarf planet is suspected to contain more freshwater than we have here on Earth, and it was thought that a meteor collision may chipped off some of the planet's surface and exposed this frozen water.

But ice is known to reflect nearly all of the light shone on it, whereas Ceres' mysterious patches only seem to reflect around 40 percent, so that idea didn't quite add up. There was also the suggestion that the bright spots might be some type of rock, or the results of geyser or volcanic activity.

Those sound like pretty cool options, but don't get too disappointed that they've been disproven. If confirmed, the presence of salt on the surface of Ceres is equally exciting, and would indicate that the surface of the dwarf planet is still active. Russell explained that they believe the salts are "derived from the interior somehow", and weren't put there by an asteroid.

Although we still know very little about the salt patches, it's possible that they may have got there in a similar way to the salty deposits recently confirmed on the surface of Mars.

And just like on Mars, there's also a good reason that we're not rushing down to Ceres to check the bright patches out - a subsurface ocean on Ceres could very well harbour life, and we don't want to contaminate it with traces of Earth.

As our editor Bec Crew wrote last week, NASA is bound by the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which forbids "anyone from sending a mission, robot or human, close to a water source in the fear of contaminating it with life from Earth".

And the type of sterilisation required to make rovers safe to get near water would also fry their hardware. "In order to be completely sterile, they'd have to use really powerful ionising radiation or heat, both of which would damage the electronics," astrobiologist Malcolm Walter told Marcus Strom over at The Sydney Morning Herald. "So they go as far as they dare."

So for now all our observations of these presumably salty patches will be made by Dawn. But as the spacecraft gets closer to the dwarf planet towards the end of the year, we'll have access to more high-res photos and hopefully more information on what's causing them.

If there's one thing we've learnt this year, it's that space has all kinds of weird and wonderful things going on, and we can't wait to find out more about what's going on out there on Ceres. Watch Russell's full opening address below: