A device that can detect gases found exclusively in the breath of people with lung cancer has been developed by researchers in China.

The low-cost screening device, which was designed and built by a team from Chongqing University in China, has 35 chemically responsive fluroescent sensors. This array of sensors has been designed to change colour when exposed even to very low concentrations of specific volatile organic compounds, or gases, which have been directly linked to lung cancer.

Previous studies have shown that there are specific gases related to lung cancer, which originate from the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acid. This occurs as normal cells transform into cancer cells and begin to form tumours. Because these gases appear only in the exhaled air of people with lung cancer, several different research teams have been targeting them as possible biomarkers for early diagnosis of the disease.

Lung cancer is the deadliest form of cancer, resulting in an estimated 1.59 million deaths annually. Current diagnostic methods include imaging techniques such as x-rays, CT scans and MRIs, but these are generally quite expensive, and some studies have suggested they're not that effective for early detection, which is crucial for improving survival rates.

So far, the team from Chongqing University has only tested their device in the lab, but their experiments have been promising: "Our results show that the device can discriminate different kinds and concentrations of cancer related volatile organic compounds with a nearly 100 percent accurate rate," said lead investigator and optoelectronic engineer Jin-can Lei, in a statement prepared by the American Institute of Physics (AIP). "This would also be a rapid method in that the entire detection process in our experiment only takes about 20 minutes."

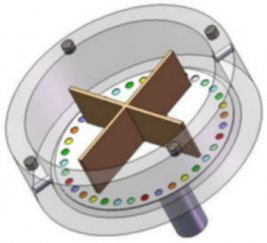

The new breathalyser device, developed by Lei and his colleagues, has a rotating chamber, which evenly distributes the gas molecules across 35 chemically-responsive sensors, located around the edge of a 5-cm-wide circular plate inside. A light source then produces three lasers with different nanometre wavelengths, which excite the fluorescent spectra of the array of sensors. By collecting the "initial" fluorescent spectrum of the array before exposure and the "final" spectrum, the researchers can identify and quantify a specific gas.

In their most recent experiment, the team looked at four gases known to be present in the breath of people with lung cancer: p-xylene, styrene, isoprene and hexanal. Using their device, they were able to consistently discriminate between the four gases with high accuracy, and quantify how much of each gas was present in the sample, even at concentrations as low as 50 parts per billion.

The team has described their breathalyser device and published their findings in the AIP journal Review of Scientific Instruments, where they noted that "the proposed detection device has brilliant potential application for early clinical diagnosis of lung cancer."

The researchers say their next step is to refine the method and establish a complete fluorescent database for lung cancer-related gases.

Breath tests for lung and other types of cancer could play a big role in the future after another breathalyser device, developed by a UK-based company called Owlstone Nanotech, was recently approved for clinical trials.