Researchers have found a way to adjust a material so its stiffness can shift between that of soft rubber and hard steel – simply by placing a small amount of stress on it.

This new design for metamaterials – materials engineered to have properties not found in nature – could have all kinds of uses, such as airbags built right into the fittings of a car, or bicycle tyres that automatically adjust their firmness.

What makes the approach particularly promising is it that it stands up well to repeated transformations – not causing any damage to the components that make up the material – and doesn't use up much energy.

"The novel aspect of this metamaterial is that its surface can change between hard and soft," says physicist Xiaoming Mao from the University of Michigan.

"Usually, it's hard to change the stiffness of a traditional material. It's either hard or soft after the material is made."

Think dental fillings – their integrity can't be altered after they're set without some serious drilling and grinding from a dentist.

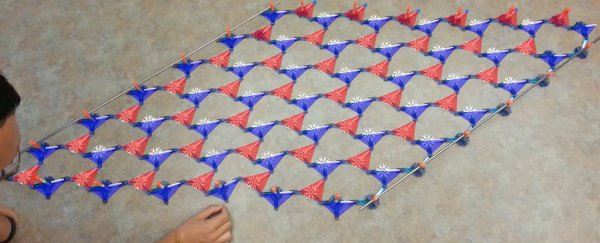

With the technique Mao and his colleagues have devised, those rules of nature don't apply. As their demo video shows, the geometry of the new material is based around a lattice of tiny struts held with connecting hinges:

As the lattice structure comes under strain, it changes the surface properties of the material, so it becomes harder or softer around the edges.

But with the hinges taking all the strain, the main structure can remain intact – it's topologically protected, in the words of the researchers.

The new design could pave the way for rockets that stay rigid as they take off, then become softer when they come into land, or for car steering wheels made to absorb pressure in a crash.

"When you're driving a car, you want the car to be stiff and to support a load," says Mao. "During a collision, you want components to become softer to absorb the energy from the collision and protect the passenger in the car."

While it's still early days for this type of metamaterial, the potential uses are certainly enough to get us to sit up and take note, and are the latest in a long line of innovative uses for synthetic materials.

The properties of these kinds of metamaterials are defined not just by the building blocks used to make them, but also by how those building blocks are put together – which helps scientists create materials that do things like hide from radar or change their state when heated or cooled.

It's pretty amazing stuff – and if your next car can absorb the impact of a crash all by itself, without needing a separate airbag to protect you, you'll know who to thank.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.