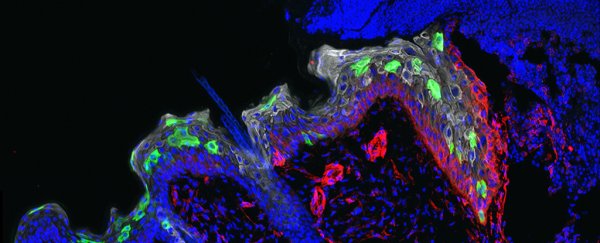

Wounds, and even other harmful attacks that cause inflammation, are 'remembered' by stem cells in the skin, according to new research, and those 'memories' are used to heal our bodies faster the next time around.

While stem cells don't suddenly have brain-like memory-forming capabilities, this research has shown these amazing cells log past experiences to improve their wound-healing capabilities in the future. And at times this ability could actually have a negative result.

It's the first evidence we have that the skin can form memories of an inflammatory response, and it could help experts improve their understanding and treatments for a range of conditions, say the researchers from Rockefeller University in New York.

"By enhancing responsiveness to inflammation, these memories help the skin maintain its integrity, a feature that is beneficial in healing wounds after an injury," says one of the team, Elaine Fuchs.

"This memory may also have detrimental effects, however, such as contributing to the relapse of certain inflammatory disorders such as psoriasis."

In the case of psoriasis, where the life cycle of skin cells is sped up and causes scaly and itchy skin, the new findings could be used to figure out a way to slow down the skin's rapid response and control the problem.

We've long known that the immune system keeps a record of inflammatory incidents so the body can be better prepared next time, but it appears the skin has a similar mechanism, and that has implications for other areas where these types of stem cells are used for repair, like the gut and bowel.

"Inflammatory diseases have long been blamed on immune cells that turn against the body," says one of the researchers, Samantha B. Larsen. "However, that is clearly not the only cause: stem cells may also be important contributors."

Tests with mice showed that wounds closed more than twice as fast on skin that had been damaged before, even if the original inflammation was as far back as six months (roughly equivalent to around 15 years for a human).

The results indicate the battle-hardened stem cells became better at moving towards a wound to heal a breach the next time around.

Further experiments showed that inflammation triggered a process where certain genes within the cell's chromosomes became more accessible and stayed more accessible, so they could be switched on faster for future inflammations.

To put it another way, the inflammation puts cells on high alert – and to some extent they then stay that way.

In particular, the Aim2 gene, responsible for a "damage-and-danger" sensing protein, was noted as being important to the whole process. Through being activated after the first inflammation, it could quickly give the healing stem cells a boost on their next trip.

Most of the cells on our skin don't stick around long enough to remember such infections, before they get shed from our bodies, but the stem cells deeper within the epithelium do, the researchers discovered.

All of which is very helpful for scientists working out exactly what happens when we get a paper cut, or a sunburn, or anything else that causes inflammation. Not only for protecting against attack in the normal way, but also fighting against diseases that hijack the inflammatory process.

"A better understanding of how inflammation affects stem cells and other components of tissue will revolutionise our understanding of many diseases, including cancer, and likely lead to novel therapies," says one of the team, Shruti Naik.

The research has been published in Nature.