Scientists have shown that changes in rats' retinas can predict Parkinson's disease long before visible symptoms such as muscle tremors and stiffness start to occur.

If the same technique is shown to work in humans, it would offer a cheap and non-invasive way to detect the disease and start treating it before it gets worse.

The strategy requires only instruments that are currently in use by ophthalmologists, which means it could also offer an easier way to monitor how well a treatment is working for a patient.

"This is potentially a revolutionary breakthrough in the early diagnosis and treatment of one of the world's most debilitating diseases," said lead researcher Francesca Cordeiro from the University College London.

"These tests mean we might be able to intervene much earlier and more effectively treat people with this devastating condition."

Parkinson's is a progressive neurological condition that affects one in 500 people. Right now, it can only be diagnosed by a neurologist, and there's no single test or brain scan that can definitively diagnose the disease - doctors need to use a mix of different measures and tests.

The reason is that Parkinson's usually starts with small symptoms that are easy to overlook, such as slight tremors or a loss of motor control, so many people don't get diagnosed until the disease is quite advanced - usually once more than 70 percent of the brain's dopamine-producing cells have already been destroyed.

So a test that could potentially be done alongside a regular eye check-up could make a huge difference for those at risk.

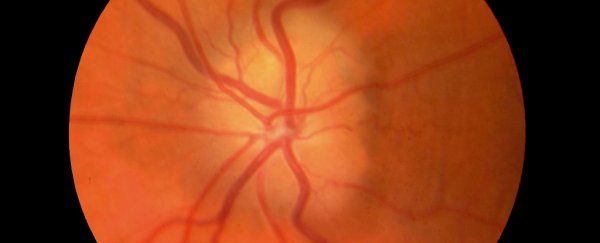

The new technique works by shining light on the back of the eye and looking at how many cells in the retina, known as retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) are going through cell death, as well as detecting signs of swelling in the region.

To figure this out, the team took rats that had been engineered to develop Parkinson's disease. They detected increased RGC apoptosis and swelling in their eyes days before the animals displayed any physical symptoms. The team reports being able to see signs of the disease in the rats' eyes by day 20, and traditional symptoms by day 60.

To take things one step further, the researchers also investigated whether treating the condition at this early stage would have any benefits.

They gave the rats a new type of anti-diabetic drug called rosiglitazone, and showed that by treating them early, they were able to effectively reduce the amount of nerve cell damage, compared to animals that didn't receive early treatment.

As we mentioned before, these results need to be replicated in humans before we can get too excited, but the team says that their results were successful enough that they'll now be pushing forward to human trials.

"Although the research is in its infancy and is yet to be tested on people with Parkinson's, a simple non-invasive test - such as an eye test - could be a significant step forward in the search for treatments that can tackle the underlying causes of the condition rather than masking its symptoms," Arthur Roach, director of the charity Parkinson's UK, told the BBC.

Their research has been published in Acta Neuropathologica Communications.