Physicists in Germany have built the most accurate timepiece on Earth, achieving unprecedented levels of accuracy with a new atomic clock that keeps time according to the movements of ytterbium ions.

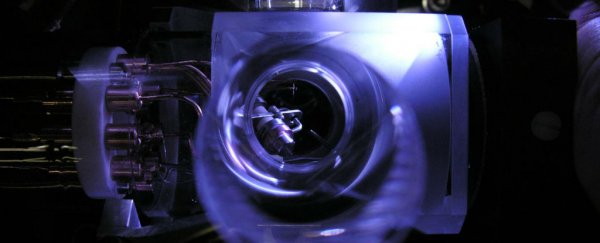

Called an optical single-ion clock, the device works by measuring the vibrational frequency of ytterbium ions as they oscillate back and forth hundreds of trillions times per second between two different energy levels. These ions are trapped within an 'optical lattice' of laser beams that allows scientists to count the number of ytterbium 'ticks' per second to measure time so accurately, the clock won't lose or gain a second in several billion years.

Until very recently, our most accurate time-keepers were caesium atomic clocks - devices that contain a 'pendulum' of atoms that are excited into resonance by microwave radiation. It's on these clocks that the official definition of the second - the Standard International (SI) unit of time - is based.

According to the most accurate caesium atomic clock in the world, 1 second is the time that elapses during 9,192,631,770 cycles of the radiation produced by the transition between two levels of the caesium 133 atom.

That might sound pretty good, but when it comes to defining time itself - the thing that governs literally everything we do in life - you can never be too accurate.

As researchers around the world have been perfecting their optical atomic clocks, the need to redefine the second according to these devices rather than caesium atomic clocks has become more and more pertinent. And especially now - seeing as a team of atomic clock experts from Germany's Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) have built one that's no less than 100 times more accurate than the most accurate caesium atomic clocks.

"It is regarded as certain that a future redefinition of the SI second will be based on an optical atomic clock," the team says. "These have a considerably higher excitation frequency (1E14 to 1E15 Hz), which makes them much more stable and more accurate than caesium clocks."

Predicted back in the 1980s by Nobel Prize winning physicist, Hans G. Dehmelt, optical atomic clocks are basically laser traps for single ions or many neutral atoms. While a number of these clocks have been built in the past, the one constructed by the PTB team is the first to attain an accuracy level that, until now, had only been predicted in theory. If you want to get technical, that means it has a measurement uncertainty of 3 E-18.

The team says that ytterbium - a soft, silvery chemical element - is the perfect type of ion for their clock, because it can transition between to states to give a clear and measurable 'tick'. "One of these transitions is based on the excitation into the so-called 'F state' which, due to its extremely long natural lifetime (approximately six years), provides exceptionally narrow resonance," the team reports.

Just like the kilogram, which is currently undergoing a redefinition of its own, everything in the International System of Units is up for grabs if you've got a more accurate way to measure it. And really, that's about as fundamental as science gets.

The results have been published in Physical Review Letters.