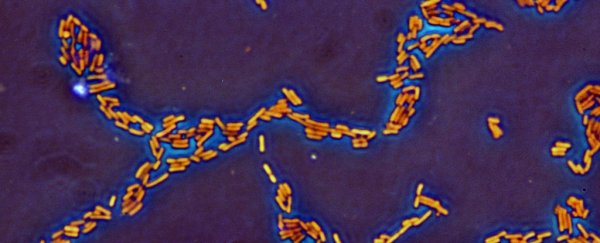

Geneticists have made a step forward in 'recoding' the genome as we know it, replacing 62,214 DNA base pairs in a synthetic E. coli genome.

Recoding genomes so extensively could lead to the development of organisms that are resistant to viruses, and could even allowing biologists to code for all-new synthetic amino acids. Essentially, it allows us to reprogram life.

"It's not easy, but we can engineer life at profound scales, even something as fundamental as the genetic code," says Peter Carr, a bioengineer at MIT, not involved with this study, told Science.

To understand what the researchers have done, we first have to have to understand how DNA works. DNA, and its four base pairs, A, T, C, and G, are translated into RNA, where the code is arranged in triplets, that each code for a specific amino acid (the cell's building blocks) the cell should use.

For example, A - G - G codes for the amino acid arginine, and C - C- G codes for proline.

"Almost all life shares a common genetic code," one of the researchers, Marc Lajoie, told Popular Mechanics. "For example, the genetic sequence A - G - G means the same thing for almost all organisms, from your cells, to a plant cell, to a yeast cell."

But there are 64 possible triplets, or codons, and only 20 types of amino acids that exist in nature. This means that three or four codons might encode one amino acid, and there's some overlap – for example, C - C - C also encodes for proline as does C - C - G, and the cell treats these codons in pretty much the same way.

Harvard University researchers have now removed some of this 'overlap' in E. coli (Escherichia coli) – by changing 62,214 base pairs, and removing 7 of the 64 codon types across 3,548 of E. coli's genes.

You might think this would be bad news for the cell, but the team has already tested 63 percent of the recoded genes they've produced, and nearly all of them have created relatively healthy E. coli.

"It is a bit surprising to see how plastic the genome could be," Patrick Cai, a synthetic biologist at the University of Edinburgh in the UK, who was not involved with the work, told The Scientist.

"It is also very exciting to see [that] technologies such as computational design, de novo synthesis and assembly, as well as a range of phenotyping assays, are now mature to support genome refactoring at this scale."

One of the most exciting parts about this work is that being able to recode the DNA in this way could lead to bacteria that are resistant to all kinds of viruses.

In an earlier paper published in Science, the team did this by removing the mechanism for the E. coli cell to be able to understand a codon – this particular one coded for the cell to stop transcribing. When they removed the protein, called RF1, when the codon, U - A - G, was read, the DNA machinery didn't stop like it usually would.

This meant that their cells read the DNA differently - if U - A - G was specifically added in later and the cell was forced to read it, it wouldn't know what to do with it, and therefore wouldn't be affected.

This forceful addition of DNA is something that happens naturally when viruses infect any living cell. They do this by splitting the host genome and adding in their own DNA - usually to produce more of the virus.

"When viruses infect a host cell, they essentially inject their genome and hijack the cell to create more viruses," said Lajoie. "Since GROs (Genetically Recoded Organisms) speak a different language, the virus's genetic instructions to replicate itself would be misread, and the virus couldn't complete its life cycle."

The researchers are hoping to eventually use these codons to create artificial amino acids in the bacteria. This would totally change the types of protein E. coli could create, and could have huge implications for manufacturing, and other industries.

But they still have to finish testing all the artificial genes, and combine the recoded genome to create one organism, but this is an interesting first step in a world where CRISPR and the genetic modification of human embryos are about to make a big impact.

"[This is] arguably the largest and most radical genome engineering project," Church told The Scientist.

"The next paper, which hopefully will be soon, will be to polish off the genome and start testing for things like multivirus resistance, seeing how many amino acids we can load up, and confirming the biocontainment."

The research was published in Science.