An international team of researchers has seen "extraordinary" results using patients' own immune cells to fight cancer. In one trial, 94 percent of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia saw their symptoms disappear entirely.

For patients with other types of blood cancer, response rates have been above 80 percent, and more than half have experienced complete remission, cancer researchers reported at the American Association for the Advancement for Science conference over the weekend.

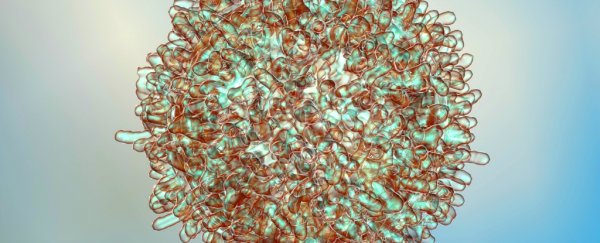

The new T-cell treatment is a type of immunotherapy, and it involves taking a patient's own immune cells - specifically, white blood cells called T-cells - and reprogramming them to attack tumours. It's sort of like creating a tailor-made vaccine response against cancer.

Scientists have been working on immunotherapy for decades, but have only recently started testing this new T-cell therapy in humans. Due to the experimental nature of the research, for now, the trials have been limited to patients who are no longer responding to other treatments, and only have a few months to live.

But results are finally beginning to emerge, and, if the conference presentation is anything to go by, the treatment has incredible potential for patients with unresponsive tumours.

"This is unprecedented in medicine, to be honest, to get response rates in this range in these very advanced patients," Stanley Riddell, an immunotherapy researcher at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Centre in Seattle, explained at the conference, as The Guardian reports.

"In the laboratory and in clinical trials, we are seeing dramatic responses in patients with tumours that are resistant to conventional high-dose chemotherapy," he added in a press statement. "The merging of gene therapy, synthetic biology and cell biology is providing new treatment options for patients with refractory malignancies and represents a novel class of therapeutics with the potential to transform cancer care."

T-cells are white blood cells that are responsible for detecting foreign or abnormal cells - including cancerous ones - and then latching onto them to tell the rest of the immune system that they need to be attacked.

Unfortunately, this immune response is often not quick or aggressive enough to get rid of fast-growing tumours. Over time, T-cells become exhausted, and some tumour types learn to evade them, allowing them to dodge the immune system altogether.

This is where immunotherapy comes in - to put the system into overdrive, scientists perform what's known as adoptive T-cell transfer. This means they first extract patients' T-cells from their blood, and, using gene transfer, introduce receptors that will aggressively target a specific cancer cell. Once back inside the body, these newly engineered T-cells regenerate to create an army of immune cells prepped to take down tumours.

Using this technique, Riddell reports that he and his colleagues have seen "sustained regression" in previously terminal cases of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.

The results have been submitted for publication, and are now undergoing peer-review, which means we can't get too excited about them just yet, and there aren't huge amount of details to go off - but we do know that the aforementioned trial with the 94 percent success rate involved 35 patients, and the blood cancer study that achieved greater than 80 percent response rates involved 40 participants.

To be clear, as promising as these results are, this therapy is never likely to be a potential 'cure' for cancer, and will most likely be reserved for the most extreme cases. This is mainly because the potential side effects are severe - during the trials, 20 patients suffered symptoms of fever, hypotension, and neurotoxicity due to something called cytokine release syndrome, and two patients died.

"Much like chemotherapy and radiotherapy, it's not going to be a save-all," said Riddell. "These are in patients that have failed everything. Most of the patients in our trial would be projected to have two to five months to live … [But] I think immunotherapy has finally made it to a pillar of cancer therapy."

Italian cancer researcher Chiara Bonini also spoke at the conference, and was more hopeful about the therapy, as The Guardian reports.

"This is really a revolution," she said. "T-cells are a living drug, and in particular they have the potential to persist in our body for our whole lives … Imagine translating this to cancer immunotherapy, to have memory T-cells that remember the cancer and are ready for it when it comes back."

Riddell's lab is now working on applying the T-cell therapy to a wider range of cancers - not just blood cancers - and is trying to make engineered T-cells safer and easier to design. The team also wants to track how long patients remain in remission following the treatment before progressing with broader trials.

We'll need to wait for peer-reviewed results before we know exactly how excited we should get about T-cell therapy, so watch this space.