In classical computing, information is stored in bits that are read by physical phenomena such as electricity. You might recognise them as 1s and 0s, also called binary code. In quantum computing, it's stored in quantum bits, or 'qubits'.

However, computers aren't the only way we can store information: chemistry is also capable.

Scientists at the Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IPC PAS) in Warsaw have developed a way in which chemical droplets can store information like bits and qubits in a one-bit chemical memory unit called the 'chit'.

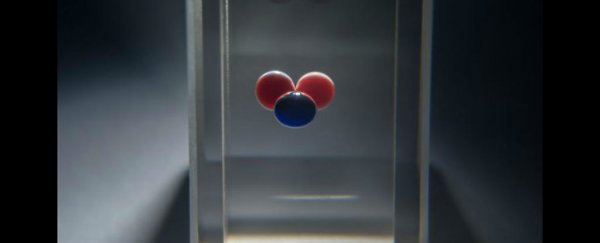

The chit is made up of three droplets. Between the droplets, chemical reactions take place, circulating cyclically and consistently. This memory is rooted in the Belousov-Zhabotinsky (BZ) reaction, which reacts in an oscillatory manner.

Each reaction creates the reagents necessary for the next reaction, continuing ad infinitum. These reactions are helped by a catalyst - ferroin - which causes a colour change.

There is also a second catalyst - ruthenium - which makes the reaction light sensitive.

It's this light-sensitive feature, when blue light is shone upon the reaction, that stops it from oscillating. That's important, because it allows researchers to control the process.

The chit essentially allows for 'chemical computing'. So, instead of traditional bits, the components are all chemical.

While quantum computing continues to advance, this brand new type of computing could create an entirely new way to store, read, and transfer information.

Everything from smartphone technology to classified digital files depend on our ability to store and read information - the basis of computing.

Completely changing the very base of most technology that we rely upon today could have incredible consequences.

Perhaps technologies that are currently being developed to battle climate change could face major upgrades and modifications.

Perhaps the devices and vehicles that we use to explore space will go through changes as well.

This type of advancement could completely revolutionise so much of the technology that we know, and in ways we may not even yet be able to imagine.

This article was originally published by Futurism. Read the original article.