An Australian researcher has used brain scans to figure out exactly what's going on during an episode of delirium - a discovery that could provide treatments for a condition first described over two millennia ago.

With up to half of all hospitalised patients over 65 affected by this debilitating neurological disorder, delirium is a serious problem in need of solution as our population ages, and it looks like low metabolism could be to blame.

Delirium is a state of extreme confusion, fluctuating awareness, and sometimes even hallucinations, often during a fever or infection. While many of those diagnosed with delirium do have sepsis, the symptoms can arise as a result of other forms of brain trauma or neurological disorders, including Alzheimer's disease.

The condition was first detailed in the 16th century, but we can go back 2,500 years ago to the famous Greek physician Hippocrates for a category of mental disorder called phrenitis, which involved similar symptoms including hallucinations and restlessness caused by inflammation and fever.

The ancient physicians pointed their finger at fluid imbalances and toxins, and while medical science has long since moved on, researchers still haven't had a clear description of the pathology behind the condition.

Recent studies had implicated a range of possible culprits, from faulty signals between nerves to hormone imbalances, to inflammation of the brain tissue.

But a bulk of research finding a relationship between delirium and reduced blood flow and oxygen saturation heavily implied that metabolism played a key role.

Concentrations of an enzyme that helps break down glucose without oxygen, and higher concentrations of lactic acid, also suggest a relationship between delirium and abnormal metabolism.

"However, as this research is scant, only includes one cause or subtype of delirium, and does not correlate anatomy with clinical features, further research of metabolism in delirium is warranted," a team led by Gideon Caplan from the Prince of Wales Hospital in Sydney wrote in a recent report.

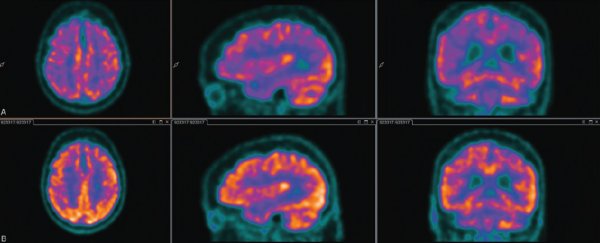

To address this, Caplan and his colleagues used positron emission tomography (PET) to take a closer look at the brains of 13 elderly patients admitted into hospital with delirium.

The scan detected the uptake of a radioactive, glucose-like molecule called fluorodeoxyglucose into the patient's neurons, resulting in a map of metabolism across their entire brains.

In particular, the researchers were interested in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) - the rear portion of a highly connected layer of tissue running through the middle of the brain that plays an important role in executive functions and awareness.

The PCC is understood to play a role in other awareness, memory, and sensory disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ( ADHD), and schizophrenia.

The researchers found various patterns of low metabolism across the PCC in the elderly patients while they had delirium.

Unfortunately, they could only conduct a follow up scan on six of the patients, but they did find that as the delirium subsided, metabolism across their entire brain and in the PCC increased again.

While the outcome seems fairly clear, it pays to keep in mind that the sample size is very small, especially among the post-delirium tests. But the results do fall in line with findings from previous studies, which is a good sign that the team is likely on the right track.

From an economics perspective, delirium costs the US over US$164 billion every year.

The condition is preventable 30 to 40 percent of the time, yet could be undiagnosed in a quarter of all possible cases - a figure that jumps up to nearly 90 percent of cases when dementia is involved.

Given we don't have any way to treat it at the moment, it's important to learn all we can about the disorder.

A trial is currently underway at the Prince of Wales Hospital to test whether insulin delivered via a spray through the nose could help increase glucose uptake in the brain.

Time will tell if the studies are sniffing in the right direction, but for now, it's exciting to be honing in on the cause of such a debilitating - and common -condition.

This research was published in the Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism.