Researchers have used brain scans and artificial intelligence to spot differences in how key areas of infant brains synchronise, allowing them to accurately predict which babies would develop autism spectrum disorder ( ASD) as a toddler.

This is the first time a single scan has been used to confirm development of the condition in children who are at risk, providing opportunities for earlier intervention and a way to better understand how autism's characteristics develop.

The research, led by scientists from the University of Carolina and Washington University, comes hot on the heels of an earlier study that used two scans taken at 6 and 12 months to make a similar prediction.

Not only has this new method reduced the number of scans required to make the judgement, they were able to predict with more than 96 percent accuracy which 6 month old infants would be diagnosed with autism by age 2, compared to 81 percent previously.

ASD is an umbrella term used to describe a range of impairments to social and communication functions, often accompanied by restricted and repetitive behaviours.

Estimates on the disorder's prevalence vary, with some reports concluding as many as 1 in 68 children under the age of 8 fall into the category.

It's unlikely that there is any single cause that can account for ASD's traits, with numerous genes, metabolic dysfunctions, and neurological 'switches' implicated.

But whatever the fundamental causes might be, until now a clear diagnosis has only been possible once a child has started to develop more complex social behaviours, usually around the age of two.

"There are no behavioural features to help us identify autism prior to the development of symptoms, which emerge during the second year of life," said researcher John R. Pruett from the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

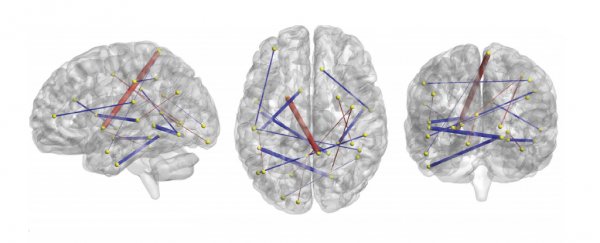

The researchers used magnetic resonance imaging to analyse the neural activity of 230 regions across the brain in 59 infants who had at least one older sibling with a diagnosis of ASD.

Specifically, rather than looking for differences in anatomy, they measured how these different areas connected and synchronised with one another.

The coordination of these regions was determined to be crucial in behaviours related to autism, such as language, repetitive behaviours, and social tasks.

Of more than 26,000 possible pairs of connections, the team identified 974 in the six-month-old infants that could be used to predict a diagnosis by 24 months, and fed these into a machine learning program.

The results were remarkable.

"When the classifier determined a child had autism, it was always right. But it missed two children. They developed autism but the computer program did not predict it correctly, according to the data we obtained at six months of age," said researcher Robert Emerson from the University of Carolina.

A larger sample size and more data will no doubt help determine just how accurate this method of diagnosis could be in the long term, which is what the researchers are planning next.

It's also unlikely that a single test will form the basis of any future diagnoses – more likely, it would form one piece in a risk profile informed by research involving a variety of evaluations.

"I think the most exciting work is yet to come, when instead of using one piece of information to make these predictions, we use all the information together," said Emerson.

ASD doesn't have a cure, but research indicates early intervention with therapies designed to assist in the development of important communication and social skills can help a child meet the challenges.

"The more we understand about the brain before symptoms appear, the better prepared we will be to help children and their families," said researcher Joseph Piven, also from the University of Carolina.

For many families at risk of having children with ASD, knowing with confidence that they'll need to prepare their young child with the skills they'll need to cope with their condition would be a massive step forward.

This research was published in Science Translational Medicine.