Scientists have found that dormant memories can be revived by delivering a pulse of magnetic stimulation to the brain, allowing people to retrieve forgotten information with almost perfect recall.

The results have revealed that a type of short-term memory called working memory could be far more complicated than we thought, and could answer some long-standing questions about what causes a number of mental illnesses.

"This changes how we think about the structure of working memory and the processes that support it," one of the team, Nathan Rose from the University of Notre Dame in Australia, told NPR.

Working memory is the kind of short-term memory that gives you the ability to remember relevant information while in the middle of an activity.

It lets you memorise a new phone number long enough to make a call, or retain the names of two new people you meet at a party while you're having a conversation.

For decades now, scientists have assumed that working memory retains information in the short-term through sustained brain activity.

It was thought that the continuous activity of a certain set of neurons was required to retain the information, and if that activity ever faulted, that memory would be lost forever.

But Rose and his team wanted to investigate how the brain determines what information to retain at any given moment, and what it ends up filing away for quick access later on.

Because while it might feel like we're able to take in a whole lot of new information at a time, our working memory is actually quite limited in what it 'chooses' to retain.

"The notion that you're aware of everything all the time is a sort of illusion your consciousness creates. That is true for thinking, too," said one of the researchers, Brad Postle from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, in a press release.

"You have the impression that you're thinking of a lot of things at once, holding them all in your mind. But lots of research shows us you're probably only actually attending to - are conscious of in any given moment - just a very small number of things."

The researchers gathered 66 participants to observe how their working memory actually functioned.

Through a number of experiments, they tested how the participants would remember sets of two different things - a face and a word. They were shown the items, then told they needed to remember them later on, and MRI scans were taken to see how the brain reacted.

"That caused a distinct pattern of activity in two groups of brain cells: one that was keeping track of the face and another that was keeping track of the word," Jon Hamilton reports for NPR.

"But then … the researchers had people focus on just one of the items they'd seen. And when they did that, the brain activity associated with the other item disappeared."

"It was almost as if the item had been forgotten," Rose said.

But when the participants were warned that they were about to be quizzed on the second item they were supposed to remember, their working memory suddenly kicked back into gear - disproving previous assumptions that the working memory had to be continuously activated.

"People have always thought neurons would have to keep firing to hold something in memory. Most models of the brain assume that," Postle explains in the release.

"But we're watching people remember things almost perfectly without showing any of the activity that would come with a neuron firing. The fact that you're able to bring it back at all in this example proves it's not gone. It's just that we can't see evidence for its active retention in the brain."

Next, the team asked the participants to focus on remembering the face, which caused them to forget about the word.

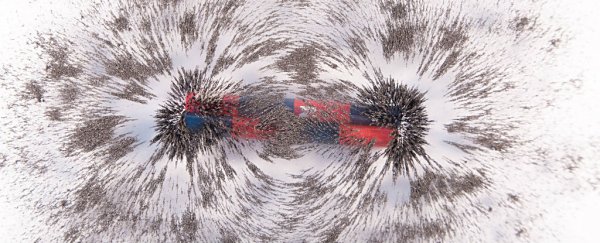

They then used a technique called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to apply a focused electromagnetic field to the exact part of the brain involved in storing the word, causing the participants to incorrectly think they'd been asked to focus on the word - not the face.

"We think that memory is there, but not active," says Postle. "More than just showing us it's there, the TMS can actually make that memory temporarily active again."

The experiments only featured a very small sample size, so it's not enough to start dreaming of a future where we can start using magnetic stimulation to recall lost short-term memories.

But the researchers say their experiment could help further our understanding of mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and depression, because it's revealing exactly how our brains decide what thoughts to focus on, and how this can be mitigated.

"A lot of mental illness is associated with the inability to choose what to think about," says Postle. "What we're taking are first steps toward looking at the mechanisms that give us control over what we think about."

The research has been published in Science.