Things are about to speed up dramatically in genetic research, with scientists developing a new technique that can clone thousands of genes in a single reaction.

The new technology, called a LASSO probe, could be used to create libraries of proteins from DNA samples, speeding up the search for new drugs by replacing the tedious methods of gene cloning currently used.

When you think of cloning you may think of Dolly the sheep or the company that promises to clone your favourite pet so you don't have to live sad and alone, but that's a different kind of cloning. Here we're talking about molecular cloning, a natural process that occurs when bacteria, insects, or plants reproduce without a partner.

Scientists clone DNA because they want to do one of two things; either they want to gain information about a particular gene or they want to manipulate genetic information in a cell to give the cell a new property. Both reasons require scientists to have millions of copies of the same DNA molecule in a test tube.

At the moment, to work out what a gene does by cloning its DNA and expressing its protein is done one gene at a time. The standard sequencing method, called molecular inversion probes, involves capturing small fragments of DNA (about 200 base pairs long) and connecting them together to map out the full genome code.

Weaving together these small sections of code to form the full gene sequence isn't easy, but there hasn't been any other way to sequence long fragments of DNA and it's been holding research back.

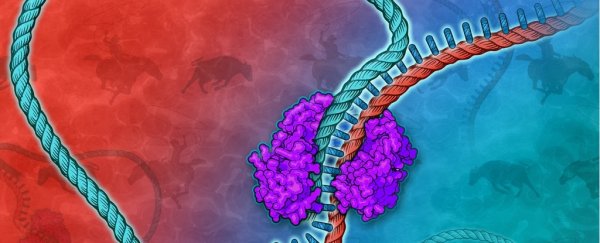

Not to scale. Credit: Jennifer E. Fairman/Johns Hopkins University

Not to scale. Credit: Jennifer E. Fairman/Johns Hopkins University

"We think that the rapid, affordable, and high-throughput cloning of proteins and other genetic elements will greatly accelerate biological research to discover functions of molecules encoded by genomes and match the pace at which new genome sequencing data is coming out," says one of the team, Biju Parekkadan, from Rutgers University.

In this new study, the LASSO probe - which stands for "long adaptor single stranded oligonucleotide" - can capture and clone thousands of long DNA fragments and the researchers hope that the new technique will push the limits of what we can currently do.

"Our goal is to make it cheap and easy for any researcher in any field to clone and express the entire set of proteins from any organism," said co-researcher Ben Larman from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "Until now, such a prospect was only realistic for high-powered research consortia studying model organisms like fruit flies or mice."

How does this new technique work?

A collection of LASSO probes were used to grab desired DNA sequences, you can think of it like the way a rope lasso is used to capture cattle. Instead of aiming for the spiky horns of a cow, the LASSO probe targets a DNA sequence up to a few thousand base pairs long - the typical length of a gene's protein code.

The study is a proof of concept, with the LASSO probes used to capture over 3,000 DNA fragments from the E. coli bacterial genome. The results show the probes successfully captured around 75 percent of the gene they targeted.

There were also other benefits to the LASSO probe technique.

The researchers say that the sequences are captured in a way that allows them to also analyse what the genes' proteins do and demonstrated this by giving antibiotic resistance to a cell that would otherwise be killed by the antibiotic.

The researchers were also able to capture and clone a protein library from a human microbiome sample and they hope that it will lead to improved precision medicine and rapid discovery of new medicines for a range of diseases.

"We're very excited about all the potential applications for LASSO cloning," said Larman. "Our hope is that by greatly expanding the number of proteins that can be expressed and screened in parallel, the road to interesting biology and new therapeutic biomolecules will be dramatically shortened for many researchers."

The study has been published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.