In what could be a major step forward in our understanding of how cancer moves around the body, researchers have observed the spread of cancer cells from the initial tumour to the bloodstream.

The findings suggest that secondary growths called metastases 'punch' their way through the walls of small blood vessels by targeting a molecule known as Death Receptor 6 (no, really, that's what it's called). This then sets off a self-destruct process in the blood vessels, allowing the cancer to spread.

According to the team from Goethe University Frankfurt and the Max Planck Institute in Germany, disabling Death Receptor 6 (DR6) may effectively block the spread of cancerous cells - so long as there aren't alternative ways for the cancer to access the bloodstream.

"This mechanism could be a promising starting point for treatments to prevent the formation of metastases," said lead researcher Stefan Offermanns.

Catching these secondary growths is incredibly important, because most cancer deaths are caused not by the original tumour, but by the cancer spreading.

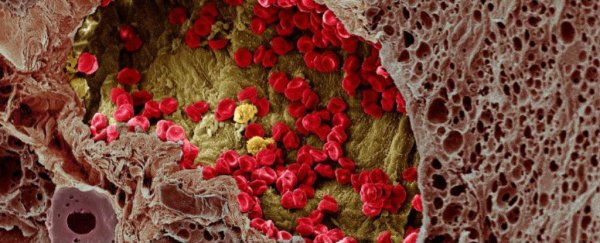

To break through the walls of blood vessels, cancer cells target the body's endothelial cells, which line the interior surface of blood and lymphatic vessels. They do this via a process known as necroptosis - or 'programmed cell death' - which is prompted by cellular damage.

According to the researchers, this programmed death is triggered by the DR6 receptor molecule. Once the molecule is targeted, cancer cells can either travel through the gap in the vascular wall, or take advantage of weakening cells in the surrounding area.

MPI for Heart and Lung Research

MPI for Heart and Lung Research

The team observed the same behaviour in both lab-grown cells and mice. In genetically modified mice where DR6 was disabled, less necroptosis and less metastasis was recorded.

The scientists have reported their findings in Nature.

The next step is to look for potential side effects caused by the disabling of DR6, and to figure out if the same benefits can be seen in humans. If so – and there's no guarantee of that – this has the potential to be a seriously effective way of slowing down the spread of cancer.

There are other hypotheses on how some metastases get around the body to cause secondary growths, though. Scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) are currently investigating the idea that tumour cells could also spread through the body outside blood vessels and the bloodstream.

The researchers suggest that a mechanism known as angiotropism could be used by some melanoma cancers to cling to the outside of blood vessels, rather than penetrating them. If this is confirmed, they would escape the effects of disabled DR6 and chemotherapy alike.

"If tumour cells can spread by continuous migration along the surfaces of blood vessels and other anatomical structures such as nerves, they now have an escape route outside the bloodstream," explained researcher Laurent Bentolila from UCLA.

The findings from that research, also conducted on mice, have been published in Nature Scientific Reports.

As the two studies show, not all cancers behave in the same way, which makes figuring out how they operate doubly difficult. But the more we come to appreciate how complex and varied this disease can be, the better chance we have of fighting it.