In 2013, a monstrous marine heatwave known as 'The Blob' developed off the coast of Alaska and soon stretched as far south as Mexico along the Pacific coast of North America.

It lingered far longer than anyone expected, decimating fisheries, triggering toxic algal blooms, disturbing kelp forests, and starving sea birds of food.

At one point, a buoy bobbing atop the ocean near Oregon detected frightening jumps in temperature of up to seven degrees Celsius in less than an hour. The ocean was sweltering.

But scientists, with their attention fixed on temperature data streaming in from ocean surfaces, had little idea what was transpiring in the depths below.

Now, new modeling led by researchers at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) shows that marine heatwaves can unfold deep underwater, too – sometimes in tandem with heatwaves that ripple across the ocean surface or else when there is no detectable warming signal above.

The new analysis, of continental shelf waters surrounding North America, also finds these so-called bottom marine heatwaves can be more intense and last longer than hot spells at the ocean surface, though it varies from coast to coast.

"Researchers have been investigating marine heat waves at the sea surface for over a decade now," says lead author Dillon Amaya, a climate scientist with NOAA's Physical Science Laboratory.

But they have been limited to the cache of data on temperature extremes at the ocean surface, logged by floating buoys or detected by ships or overhead satellites. It's much harder to probe ocean temperatures further down the water column and along continental shelves.

Some data exist, but the researchers behind this latest study mostly had to extrapolate from ocean surface observations, inputting that data into computer models to simulate ocean currents that upwell from the deep, bringing essential nutrients to coastal waters.

"This is the first time we've been able to really dive deeper and assess how these extreme events unfold along shallow seafloors," Amaya says.

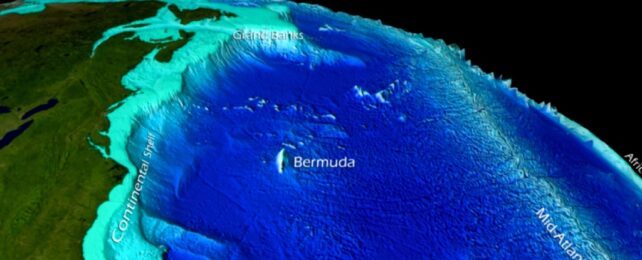

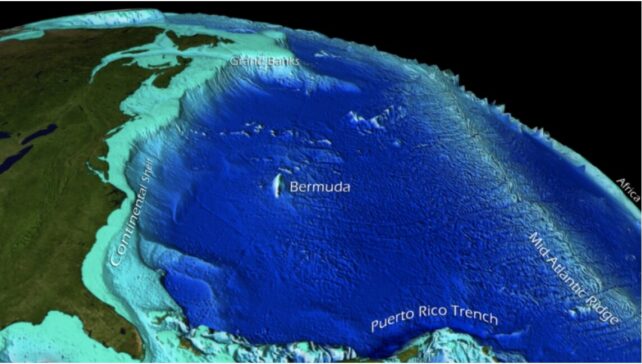

The analysis focused on the west and east coasts of North America, using data spanning three decades, from 1993 to 2019, to produce simulations with a resolution of 8 kilometers or about 5 miles, fine enough to sketch out how hot spots overlay features of the seafloor.

"Not only do bottom marine heatwaves tend to persist longer than their surface counterparts," the researchers write in their paper, "but there are many regions where bottom marine heatwave intensity tends to exceed surface marine heatwave intensity for the same location."

These two types of marine heatwaves tend to occur at the same time in shallow regions where surface and bottom waters mingle, the analysis found. Temperature spikes along the seafloor ranged from half a degree Celsius up to 5 degrees Celsius, the modeling also suggests.

But in deeper parts of the continental shelf, bottom marine heatwaves can develop without any indication of warming at the surface. "That means it can be happening without [fisheries] managers realizing it until the impacts start to show," says Amaya.

The researchers say their results underscore the importance of maintaining long-term ocean monitoring systems, especially as scientists are only just beginning to appreciate the impacts of bottom marine heatwaves.

Developing new observational capabilities to alert marine resource managers to bottom warming conditions could also help us better understand what has happened in the past – and be prepared for what's to come in the future.

Unusually warm subsurface ocean temperatures have been linked to the march of invasive lionfish into new coastal areas along the south-eastern United States, and driven the near-collapse of million-dollar lobster fisheries as lobsters' weakened immune systems come under threat from parasites.

"It's clear that we need to pay closer attention to the ocean bottom, where some of the most valuable species live and can experience heat waves quite different from those on the surface," says NOAA oceanographer Michael Jacox, who co-authored the study.

Not only that, we need to recognize that burning fossil fuels is pushing ocean ecosystems to their limits. With Earth's oceans having now absorbed about 90 percent of the excess heat from global warming, marine heatwaves like the Blob are 20 times more likely to happen.

Unlike the shadowy depths of the ocean, however, what we need to do to halt global heating is clear: End our reliance on fossil fuels and draw down carbon from the atmosphere to bring back ecosystems on the brink. The oceans can only absorb so much of our heat.

The research was published in Nature Communications.