Scientists in the US have discovered a new series of lymphatic vessels in the body that link the brain to the immune system - a connection researchers had previously thought didn't exist.

The discovery could not only prompt a rewrite of the textbooks, it might also lead to a new understanding of how our immune system influences our brain and our behaviour.

"I really did not believe there were structures in the body that we were not aware of," lead researcher Jonathan Kipnis, from the University of Virginia, told Josh Barney for the university's magazine. "I thought the body was mapped."

The new lymphatic vessels were first announced in Nature in June last year, but mostly went unnoticed by those outside of the neuroscience field.

But the discovery made headlines against last week when the team showed that the immune system could actually be controlling our social behaviour through these vessels.

The lymphatic system is made up of vessels that transport white blood cells and other immune cells throughout our body. It serves as a connection between tissues and the bloodstream, and helps remove dead blood cells and other waste.

But for decades scientists had been convinced that the brain didn't have any lymphatic vessels, and didn't have a direct connection to the immune system at all.

Along with the blood-brain barrier, this was though to keep our most vital organ safe from invading pathogens.

But, last year, the researchers showed that that wasn't the case at all - in fact, the lymph vessels had simply been hiding in the meninges - the layer of tissue that covers the brain.

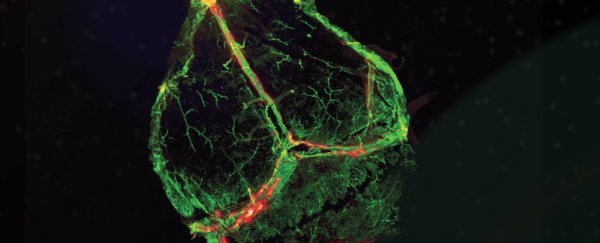

To figure this out, the researchers took entire mouse meninges and put them on a single slide - rather than slicing them up, which is how they're normally studied.

When they studied them as a whole under the microscope, the team noticed that there were immune cells spread across the sample in vessel-like patterns, and further testing revealed that these were indeed lymphatic vessels - something previous research had suggested was impossible.

The team then injected dye into anaesthetised mice so that they could show how the vessels carry fluid and immune cells from the cerebrospinal fluid, along veins in the sinuses, and into nearby deep cervical lymph nodes - a direct connection between the immune system and the brain.

The team has also found similar vessels in autopsies of human brains, but still needs to show exactly how they're organised in people, and what their function is - and finding that out could be the key to treating a whole range of diseases, from schizophrenia to Alzheimer's.

"In Alzheimer's, there are accumulations of big protein chunks in the brain," said Kipnis. "We think they may be accumulating in the brain because they're not being efficiently removed by these vessels."

The team's latest research also showed that by simply switching off one immune system molecule, they could greatly impact mice's behaviour, and stop them socialising with other mice - which suggests a role between the immune system and social conditions such as autism.

"We believe that for every neurological disease that has an immune component to it, these vessels may play a major role," added Kipnis.

There's a lot more work to be done, and the discovery of the new lymphatic vessels lead to more questions than they answer. But it's exciting to know there might now be a whole new way to approach conditions of the central nervous system.

Kevin Lee, the chair of the Department of Neuroscience at the University of Virginia, who wasn't involved in the research, recalls the first time Kipnis showed him their results: "I just said one sentence: 'They'll have to rewrite the textbooks'."

"There has never been a lymphatic system for the central nervous system, and it was very clear from that first singular observation - and they've done many studies since then to bolster the finding - that it will fundamentally change the way people look at the central nervous system's relationship with the immune system," he told Barney.

We can't wait to find out more.